Maybe “transitory” was the real transitory

Throughout 2021, there was likely no more pressing question for investors, and consumers, than this: “Was inflation truly transitory?” As described earlier, that’s certainly what the Fed wanted the world to believe.

It’s my view that high and rising inflation is the most likely factor that would terminate the Fed’s go-to reaction for nearly all threats: hitting Control + Alt + Print. This is because printing more trillions from its Magical Money Machine would only escalate inflation anxiety if it was thought to have become entrenched. Without the Fed downside protection mechanism (that now legendary Fed Put), both stocks and bonds would have to sink or swim based on actual fundamentals and free-market demand. For financial markets, this would be a most disruptive development. As you may have observed, these interrelated events are beginning to play out in early 2022.

So far in this book, I’ve just touched on inflation other than arguing that conditions are much different than in the past 40 years and, of course, in Chapter 6, that history is clear that Modern Monetary Theory-type policies are inherently inflationary. Now, though, let’s consider in detail the manifesting array of more conventional inflation forces. Far from trivial, you will see they are, in fact, paradigm shifting.

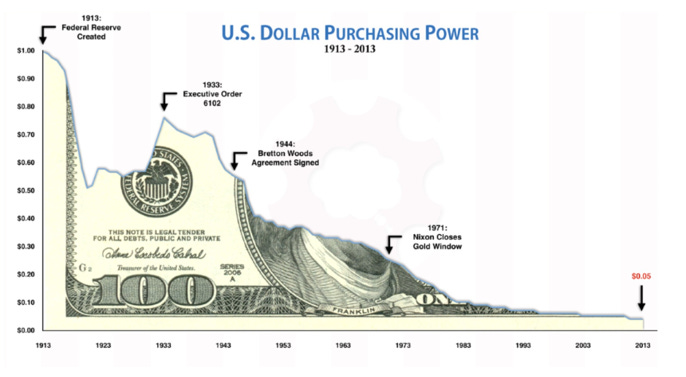

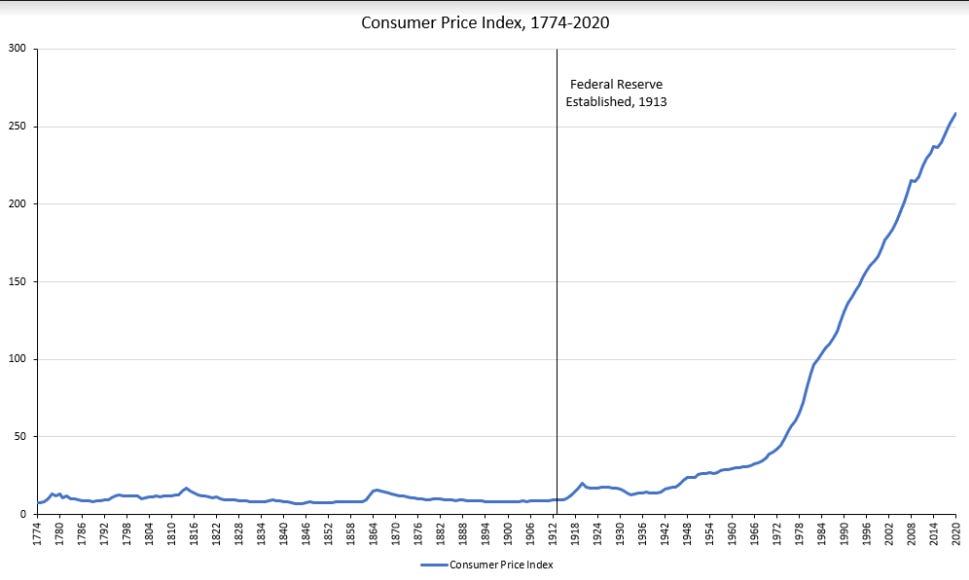

It’s sobering to consider the two images below, especially in the context of four decades of relatively benign inflation. Clearly, something big happened in the early 1970s and, as noted earlier, that was Richard Nixon pulling America off the gold standard.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Equally obviously, a game-changer also occurred right before WWI. If you’re not sure what that was, please allow me to remind you this was when the Federal Reserve was established. As you can see, basically from the founding of the Republic until the establishment of the Fed, the U.S. dollar held its own in purchasing power, except during the Civil War. Even that erosion was reversed in fairly short order due to a number of years of deflation. It’s important to point out that America enjoyed unprecedented growth in its economy during its first 130 years of existence, prior to the Fed’s creation, despite many boom-and-bust cycles.

Of course, since 1971 and the departure from the gold standard, the greenback’s decay has become even more pronounced. Yet, most Americans have felt comfortable with the Fed’s target of 2% per year purchasing power erosion despite that it means a 45% haircut over a 30-year period

Maybe that sanguine attitude was due to the fact that, as we’ve seen in earlier chapters, for most of the past 40 years it was possible to earn more than inflation with bonds and, often, federally insured certificates of deposit. But, as we all painfully know now, those days are long gone.

Frankly, that’s a big part of the inflation resurgence thesis of which I have become an ardent proponent. Millions of investors and savers are waking up to the reality that holding U.S. dollars, even including earned interest (such as it is), is a losing proposition. Thus, it’s much better to play the stock market or buy hard assets, like real estate, or not-so-hard assets, like cryptos, rather than stay in cash. When expectations become widespread that cash is trash, inflation can quickly become a societal problem.

By the fall of 2021, this had become a major consideration due to the fact that U.S. households were sitting on around $2.5 trillion of excess savings[i] and inflation was worsening, despite the Fed’s constant protests to the contrary. This massive savings cache had been accumulated since Covid blessed us with its presence and was a direct function of the federal government’s trillions of support payments. With Delta and then Omicron keeping things subdued in the second half of 2021, that money didn’t move much, other than into stocks, cryptos and other risky assets. However, given American consumers’ propensity to do what they do best — consume — I suspect this immense stash of cash won’t remain dormant. This is likely to be especially the case if Mr. and Mrs. America believe they better buy now because almost everything will cost more next year or, even, next month.

When Fed chair Jay Powell was getting grilled in Congress in July 2021 — as it was becoming obvious inflation was running much hotter than the Fed had anticipated – Senator Cynthia Lummins pointed out to him that U.S. households “… are sitting on deposits and close substitutes of equivalent to 79% of GDP” up from an average of 51%. “Is it really wise,” she went on to ask him, “to continue to have accommodative policy where there’s still trillions of household cash that will flow into the economy soon?” Mr. Powell looked at his watch as she was speaking and obfuscated as he has done so often in recent years – not to mention repeatedly contradicting himself, even in the same speech or reply. (Source: Grant’s Interest Rate Observer)

As far back as the summer of 2020, Wharton Professor Jeremy Siegel, well-known for his typically rosy view of the economy and the stock market, was picking up on the mounting inflation threat. Per Prof. Siegel, “The money created by the Fed is not going only into excess reserves of the banking system (as it did in the earlier QE rounds). It is going directly into the bank accounts of individuals and firms through the US Payroll Protection Plan, stimulus checks and grants to state and local governments”. He presciently predicted “… an extremely inflationary economy in 2021”, as early as mid-2020, per the above, when almost no one, including — make that, especially – the Fed, saw it that way.

The official inflation numbers during the second half of 2021 were certainly husky but it’s perhaps a stretch to call them “extremely inflationary”. However, Jeff Gundlach opined in his September 2021 webcast that if housing price increases were included, the CPI would be ripping at 12%, a number that certainly qualifies as extremely inflationary. This relates to my earlier examination of how the Fed’s OER (Owners’ Equivalent Rent) has understated the stunning increase in home prices this century/millennium.

Mr. Gundlach, the reigning King of Bonds, also believes the triple whammy of trillions of Federal red ink, financed by trillions of the Fed’s fantasy funds, and a hemorrhaging trade deficit, are going to be Kryptonite to the mighty U.S. dollar. Again, looking back over the last 40 years, the dollar has been strong against most major currencies. That has definitely helped keep inflation at bay.

The odds stack up against transitory

Should the buck fall hard, as Mr. Gundlach believes (in the summer of 2021 he referred to it as doomed, long-term), this will be another source of upward pressure on the CPI, as well as the PPI, the Producer Price Index. This is a function of the reality that a weaker dollar pushes up the price of imported goods.

Then there is the Fed itself and its changed and expanded mandates. It has been LCD clear that it will let the economy run hot to bring down unemployment. As a reminder, since 1978 its mission statement has been to keep inflation in-check and the jobless rate subdued. Now, the latter appears to be Job One and the former… well… not so much. This is despite the fact that, toward the end of 2021, Jay Powell began to pay lip service to controlling inflation — even as he maintained the easiest monetary policies in U.S. history, save for a few months earlier.

In my view, Powell & Co. would be well-advised to deeply reflect on this quote from former senior Fed official, William Poole: “The idea that we can let down our guard on inflation to increase employment is unwise in the long term because higher inflation eventually destroys rather than creates jobs.” (Emphasis mine) It’s a lesson that central bankers — and the planet — learned the hard way in the 1970s but, apparently, it has been unlearned in recent years.

Moreover, as I’ve also described in earlier chapters, the Fed is now under extreme political pressure to fight climate change and address racial economic inequities. On September 15th, 2021, a bill was introduced in Congress that would force the Fed to punish banks for lending to fossil fuel producers. (More on this in Chapter 9).

As far as narrowing the wage differential between whites and minorities, the Fed has made it clear it sees keeping the unemployment rate down as critical to this, even if it means more inflation. Perhaps that is admirable from a social justice standpoint, but it’s for sure another upward force on consumer prices. Moreover, there is the critical issue that the poor suffer the most from inflation surges. In his January 6, 2022, “The Flow Show” BofA’s Michael Harnett noted that “the price of basic human needs such as food, heat, shelter (are) soaring; global food price rose 27% year-over-year; US heating costs up 30% for natural gas, 43% for oil, 54% for propane; US rents up 12%, house prices up 18%.” Attempts to mitigate these hardships with wage and price controls, which might be poised to make a comeback in modern day America, are notoriously counterproductive. (Please see the Appendix for additional thoughts on this topic.)

Quoting my digital mate and fellow financial newsletter scribe, Sydney-based Gerard Minack: “The fact that the Fed has promised not to be pre-emptive in this cycle is the single most important reason to expect a second wave of inflation.” By “second wave”, he’s making the crucial point that during the first part of 2021, the CPI surge was due to commodities, like lumber, going vertical along with new and used cars. He correctly foresaw those pressures easing. This backing off caused many in the investment community to take it as validation of the Fed’s transitory thesis, at least for a while.

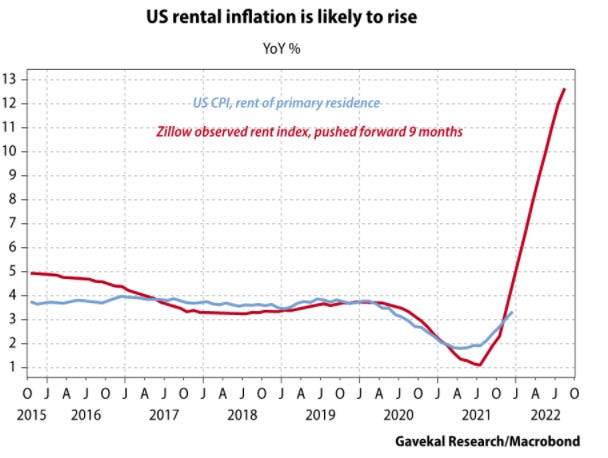

Yet, like me, Gerard sees this as a head-fake, hence the second wave part of his argument. He anticipates rent inflation to become a far more persistent inflationary impulse along the lines of a looming spike by the aforementioned OER.

Figure 3

(Source: Gavekal Research)

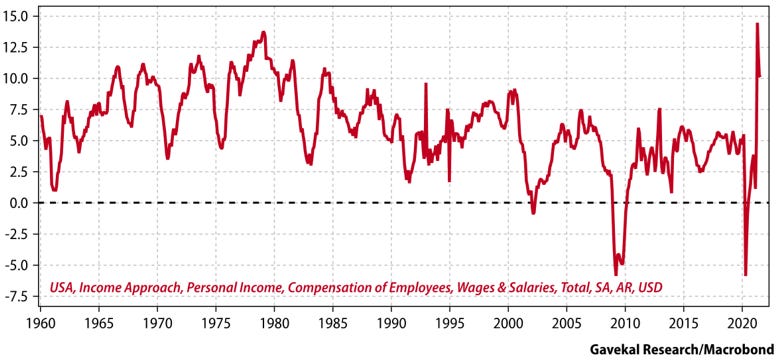

Moreover, also simpatico with this author, Gerard thinks labor costs are heading in a decidedly northerly direction. As he wrote in his July 20th, 2020, Down Under Daily, (definitely not a “DUD” of a read, by the way): “For now, signs of a tight labor market are everywhere but in the wage statistics.”

Perhaps that’s because of the archaic way they are measured. Another financial newsletter compatriot is Ben Hunt of Epsilon Theory. He contends that the U.S. generated more wage inflation over the four quarters from March of 2020 to March of 2021 than at any time in the prior four decades. Ben believes the Bureau of Labor Statistics is understating wage inflation by using a century-old approach of tabulating hourly wages versus today’s far more prevalent salary-based compensation. The following Gavekal chart certainly indicates that Ben, and Gerard, are on the right scent.

Figure 4

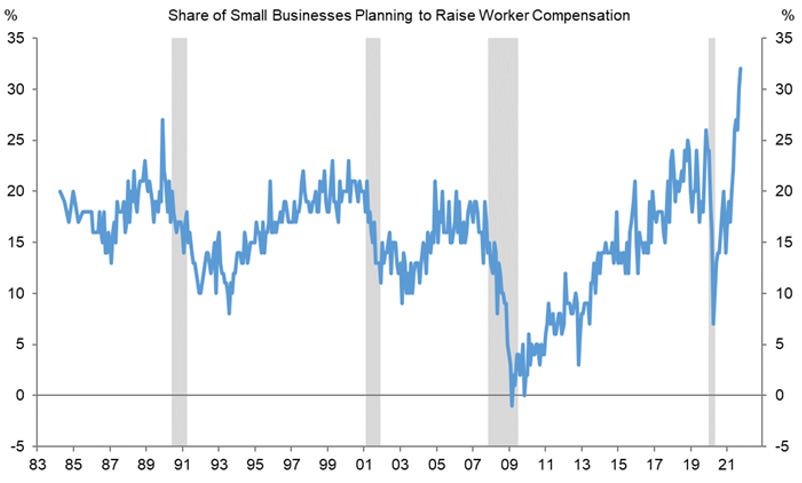

François Trahan, voted the number one portfolio strategist on Wall Street for 8 of the 10 years from 2009 to 2018, pointed out in a September 2021 research missive that the supply of labor leads wage inflation by about a year. Wage inflation, in turn, leads core inflation by another year. Based on the extremely tight job market as the year progressed, with small business openings at a two-decade high (by far), there would appear to be considerable wage inflation in the pipeline, as the below chart clearly indicates. This will make a significant CPI cool-down even less likely in 2022.

Figure 5

(Source: Goldman Sachs, 11/18/21)

My close friend Vincent Deluard, Director of Global Macro at International Stone X, believes the Fed is overlooking a critical change in the overall employment situation. In cliff note form, he is convinced it is missing the millions who are now employed in the “gig” economy, such as folks working for Uber. These individuals typically don’t have income tax withheld and, in many cases, might not report their income at all if it is paid in cash.

Yet, millions must be reporting their earnings because, per Vincent, in the first half of 2021, the Treasury collected $308 billion in non-withheld personal income taxes, up 110% from 2019! Another shocker is that this number was materially larger than the $230 billion the U.S. treasury brought in from corporate taxes in the first half of 2021. As he concedes, not all non-withheld personal income tax is from gig workers but the fact that this number exploded as the gig economy took off certainly indicates it’s been a big factor.

Vincent further observes, “Yet, the statistics the Fed uses to model the economy ignore this massive and soaring portion of the economy… The Fed’s lack of data on the… gig economy will likely lead it to overestimate the slack in the labor market.” If he’s right, and his logic is persuasive, the Fed has been making a prodigious mistake by continuing to print $120 billion a month throughout almost all of 2021 in its attempt to force down the unemployment rate when the labor market is already speedo-on-a-Sumo-wrestler tight. This has significant inflationary implications.

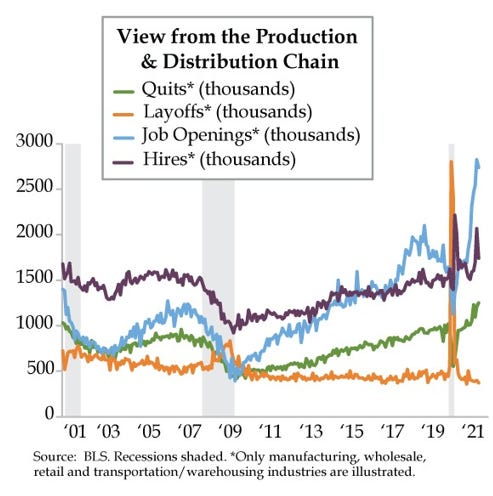

To put more color on just how robust the U.S. employment picture was in the fall of 2021, job openings were nearly 1 million above new hires, a record spread. Additionally, the Quit Rate, which measures those workers voluntarily leaving their current employers, presumably for higher pay in most cases, has been in a powerful uptrend.

Figure 6

Then, of course, the federal government has been paying generous unemployment benefits, creating a disincentive to return to work. The support payments were essential during the worst of the lockdowns. However, even early in 2021 there were countless businesses — large, small and in-between — desperate for workers, causing this policy to become exceedingly counterproductive. Unquestionably, it is yet another factor contributing to a severe shortage of employable individuals.

There was another force lurking in America’s labor market at the time, one that threatened to make conditions even more nightmarish for businesses, including hospitals, to retain their workforces. It’s a trend that pundits like Luke Gromen began referring to as “The Great Resignation”.

This referenced the swelling wave of American workers refusing to be vaccinated and choosing to retire or, I suspect, in millions of instances, opt to work in the aforementioned gig economy. The latter might not be quite as deleterious as the former because theoretically jobs are still being filled even if they aren’t part of the official economy. By the time you are reading these pages, we’ll know how great — or un-great — this resignation movement became but I would venture to say it will be another blow to keeping wage inflation in check. As I write these words, it’s hard to find a company that isn’t desperate for workers. In reality, they were often so hard-up they were forced to shut down, or, for with the means, to dramatically raise compensation.

The remarkably lucrative settlement John Deere workers agreed to in late November 2021 is a graphic, and most telling, example of the latter. Its union was able to secure for its members an upfront 10% raise, an $8500 signing bonus, further 5% pay bumps in the third and firth years of the six-year contract and 3% hikes in the second, fourth and sixth years.

Yet, the biggest eye-opener, at least to me, was that this deal reinstituted a cost-of-living adjustment, also known as a “COLA”. These were a hallmark of the inflation-riddled 1970s, but they had largely faded away since the 1980s. The fact that these are making a comeback is extremely ominous from the standpoint of avoiding the dreaded wage-price spiral. Even in Europe, where chronically high unemployment has kept a tight lid on labor costs, COLAs are reappearing.[ii]

Of course, that’s what the Fed wants: higher pay for the rank and file. The problem is that, as many began to notice during the early fourth quarter of 2021, inflation was eating up all or more of the wage gains. Rising compensation only helps workers if it outpaces the CPI which, for all the reasons we’ve seen, has become a steep hill to climb.

Further complicating this situation was a supply chain that was snarled beyond anything seen before, at least in peacetime. Rather than getting better, as it was supposed to, by the fall of 2021, it further seized up. Shipping behemoth UPS announced as the third quarter drew to a close that the logistics industry expected 2022 to be as challenged as 2021. As one wag noted around this time: “How can inflation be transitory if supply chain disruptions are here to stay?”

Further putting lasting upward pressure on prices was the passage of the contentious Infrastructure Bill that finally was signed into law in November 2021. Undoubtedly, America needs a big-time refresh of its roads, bridges and airports but the timing of this legislation is problematic. With almost all resources in tight supply and the acute shortage of workers, this legislation is highly likely to shovel more fuel into the inflation blast furnace.

On top of that, there was the even more controversial spending package — the now notorious Build Back Better (BBB) – which was first proposed by Bernie Sanders with an initial $6 trillion price tag. Moderates in Congress whittled that down to a still jaw-dropping $3 trillion. Fortunately, at least for the struggle against even higher inflation, the BBB push stalled at the end of 2021. However, the effort to pass it will likely resume in 2022. Accordingly, the jury is still out as I write this chapter as to whether this will be yet another inflation impetus.

There is little doubt that the various spending packages amounted to a massive overstimulation of the economy, generating a tsunami of additional demand in an already supply-challenged economy. It’s my prediction that the impact of this will persist not only into 2022 but for years to come.

Essentially what we did by practicing de facto MMT was to replace the normal tax-and-spend cycle that Democrats typically resorted to when they were in power — and the GOP wasn’t much, if any, more restrained – with a new model of spend-and-print. Once again, this started under Donald Trump, but Covid gave the perfect cover for it to be taken to an almost incomprehensible level. As Ben Franklin warned 250 years ago, “When the people begin to think they can vote themselves money, it will herald the end of the Republic.” Mr. Franklin didn’t know about MMT, at least by name, back then, but he was fully aware of what happened in France a few decades earlier thanks to the French monarchy’s dalliance with John Law’s version, as described in Chapter 6.

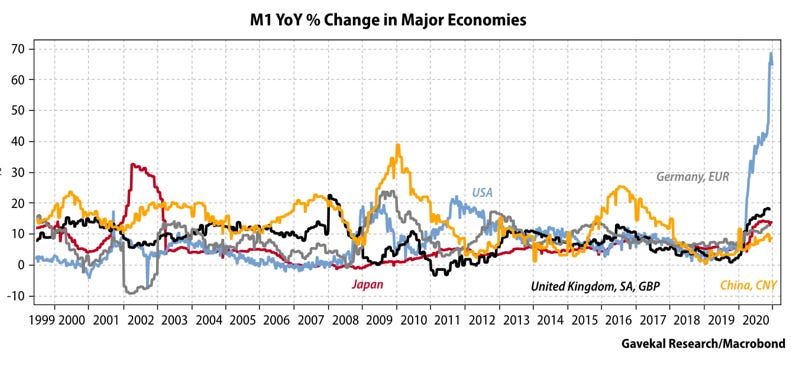

This unprecedented overstimulation of the economy revealed itself in the U.S. money supply as it inflated by 33% in less than 18 months, the greatest surge in 150 years, going all the way back to the Civil War era. Even when compared to Japan’s desperate attempt to print its way out of deflation in the early part of this century, what the U.S. money supply did was stunning. Further, there was no effort to remove that money from the system, meaning it will linger there for years to come, with all its inflationary potential.

Figure 7

(M1 = Basic Money Supply)

As we’ve seen earlier in this book, negative real rates, such as prevailed through 2021 and are almost certain to persist in 2022, are also inherently inflationary. As Charles Gave has often pointed out, a prime reason they stoke inflation is that they encourage the leveraged purchase of existing assets (like stocks or cryptos bought on margin and, of course, debt-financed real estate) at the expense of making long-term, productivity-enhancing investments such as new plants. Perhaps that’s why capital spending has been deficient for many years per Chapter 7.

Are you getting the sense yet that the Fed’s transitory story might just have a few holes in it? Well, there’s more — even before we get to the hurricane-force inflation-driver in Chapter 9. Louis Gave has pointed out that China’s One Child policy is coming home to roost. As previously discussed, China and its rock-bottom labor costs, were a significant and structural deflationary factor for at least 20 years. This was in no small part due to the fact that its labor force was growing by 10 to 15 million workers every year.

Now, though, thanks to its looming population shrinkage due to One Child, it is set to contract by 5 to 10 million annually. As Louis notes, this is a classic example of a government intervention that has gone awry, at least if you want to believe the transitory inflation narrative. With big government on the rise pretty much everywhere in the world these days, that’s yet another inflationary force. (To access excerpts from Louis Gave’s essay on how China’s demographic challenges will influence global labor costs, please see the Appendix.)

From delight to fright

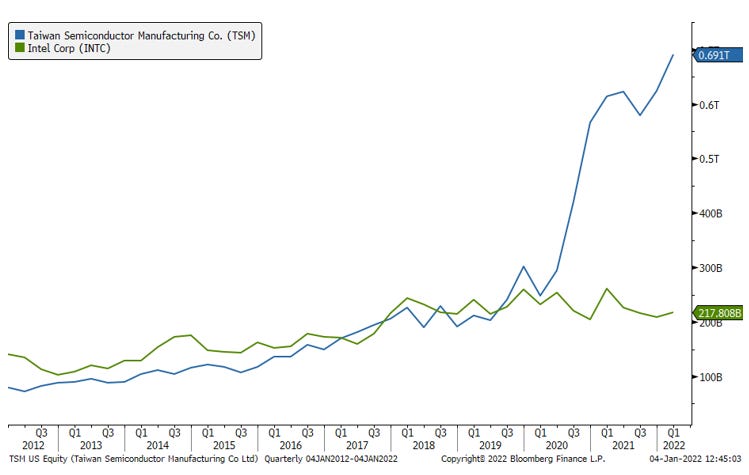

It’s a similar story with the all-important semiconductor supply situation. The China trade war that started under Donald Trump, which denied Chinese tech companies access to critical American components such as semis, caused its government to launch a frantic effort to build its own semiconductor industry. One reason being floated for why China might invade Taiwan is to secure control over the most valuable and cutting-edge integrated circuit company in the world, Taiwan Semiconductor. As you can see, Taiwan Semi’s market value now greatly exceeds Intel’s, reflecting the former’s increasing dominance.

Figure 8

In turn, the U.S. is pressuring companies like Intel and Taiwan Semi to build new plants in the U.S. to ensure access to this basic building block of nearly all things tech related. Accordingly, supply chains are being shortened, by bringing production closer to end markets. However, this has the effect of making products, including semis, more expensive. Illustrating this was Taiwan Semi’s 2021 price hike, so unusual in the tech world where, historically, prices have typically consistently gone down.

A wide range of Asian tech players are raising prices, a previously unheard-of development. Moreover, there is an acute shortage of semiconductor substrate in the autumn of 2021. Our excellent tech analyst, Arnaud Legland, sees an extremely tight market for another critical semi component, wafers, starting in 2022 with little hope of new supply coming on-line anytime soon. (Arnaud does see a number of semi products becoming oversupplied as 2022 matures.)

As Pimco’s former CEO Mohamed El-Erian wrote in the Financial Times in September 2021, “The dominant structural theme post the financial crisis — that of deficient aggregate demand — has given way to frustrating supply rigidities. They are not going away soon.” (Emphasis mine) If he’s proven right over time, as I clearly think he will be, this is highly likely to be a concussing shock to most investors who, as I’ve conveyed, remain convinced the Fed has the inflation situation under control. This is true even as Jay Powell reluctantly conceded in December 2021 that the term “transitory” needed to be “retired”. However, it’s those kinds of unpleasant epiphanies — when the majority of investors realize they’ve been betting on the wrong horse, like inflation coming down to around 2% by the end of 2022 — that create market convulsions.

This pervasive faith in the Fed has long puzzled me. As The Wall Street Journal pointed out in a July 29th, 2021, opinion piece: “The Federal Reserve employs hundreds of economists whose job is assessing the American economy. So it is remarkable that the Fed is so wrong so often in its economic forecasts. The latest big miss has been its failure to anticipate this year’s surge in consumer prices.”

Unlike the Fed, I did believe inflation was coming our way soon. Here’s what I wrote in the Evergreen Virtual Advisor (EVA) newsletter as far back as late October of 2020, when inflation was still MIA: “With Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) giving US politicians from both parties the greenlight to spend like they never have before, at least in peacetime, financed by the Fed’s MMM[iii], it’s just a matter of time, in my opinion, before we have both a weaker dollar and higher inflation. Policymakers might be delighted at first with inflation moving above 2% but when and if (I think it’s when, not if) it hits 4% or even 5%, that delight is going to turn into fright very quickly.”

It was a good, but not perfect, call: While inflation did move into the 4% to 5% range — actually, nearly 6% based on the social security hike – the U.S. dollar performed remarkably well in 2021. This is almost certainly due to the fact that most major Western countries pursued similarly incontinent fiscal and monetary policies. However, China and Russia — our, once, present, and future geopolitical rivals — have not been; thus, it’s interesting that the Renminbi rose slightly vs the USD in 2021 while the Ruble was essentially flat. Against most other currencies, the dollar rose throughout 2021.

Figure 9

Also, while it’s true a number of influential individuals began to publicly express concerns about inflation, the Fed was able to convince most politicians, and certainly the markets, that it’s a fleeting phenomenon, despite the trash-canning of “transitory”. However, former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers was not one of them. In the summer of 2021, he warned, “The Fed has had almost no success in bringing down prices once the economy has overheated.”

Regardless, the Fed has repeatedly and vehemently told the world it has all the tools it needs to bring inflation back down should it prove sticky. To which I say, “No way, Jay!” It has been my view that the Fed lacks the fortitude to take the type of extreme tightening needed to rein in truly virulent and persistent inflation. In fact, I believe Jay Powell has become the anti-Volcker.

Moreover, at this juncture, I have begun to suspect the Fed wants much more inflation than it has admitted — as long as it convinces the rest of the world of the opposite. The aforementioned Luke Gromen wrote extensively on this even before Covid hit. His basic view, in short form, is that the only way the U.S. government can cope with its nearly $30 trillion of official debt, and the off-balance sheet $100+ trillion (note the plus sign) of entitlements, is to do what America did after WWII.

Essentially, the U.S. kept interest rates low (as was the case in 2021, the Fed bought bonds to keep rates suppressed) while the economy boomed and inflation soared. The CPI rose by 20% at times in the late 1940s but interest rates were held in the 2% to 3% range. The economy grew by an average of 7.2% from 1946 to 1952 on a nominal (i.e., including inflation) basis. As a result, the debt-to-GDP ratio fell from about 115% to roughly 70%. In other words, the strategy worked, and a debt crisis was avoided. Of course, bond investors were the sacrificial lambs, as inflation destroyed the purchasing power of their holdings.

Per Luke Gromen: “When the US government borrows from its own domestic investors at negative real rates, the US government is actually stealing real wealth from its own citizens (effectively a sort of tax increase on a real basis).” He also wryly, but rightly, observes that: “Importantly, a key part of inflating away one’s debts is convincing one’s creditors that one is not inflating away one’s debts.”

To that last sentence I would add: like convincing them that the current high inflation rate is abnormal, even if no longer transitory. In Chapter 9, I’ll finally address the intense inflationary force that I believe ranks right up there with MMT in undercutting the Fed’s “we’ve got this” storyline.

[i] In other words, U.S. consumer savings has increased by around $2.5 trillion since pandemic began.

[ii] Vincent Deluard is one of the few pundits I know making the important point that COLA adjustments on social security payments are creating a much broader wage-price spiral than is generally understood. Even though these benefits are not technically wages, the inflation impact is the same. With tens of millions of now retired Boomers, and another nine million Americans disabled, thus collecting benefits, this equates to around 40% of America’s labor force. Accordingly, COLAs have quickly become extremely pervasive… and inflationary.

[iii] Its Magical Money Machine, as described earlier.