Behind Every Great Bubble Stands… A Surprised Central Bank

Chapter 16, Complete

A creature from crises past

To kick off this critical chapter, one of the most significant of Bubble 3.0, let me make clear that I believe the men and women who run the Fed are honorable and well-intentioned. I also believe they need to take responsibility for the chain reaction that I described in the Prologue:

1. Allowing the tech mania in the 1990s to inflate into the biggest equity bubble ever, at least up to that time (Bubble 1.0).

2. In response to the mild recession this crash precipitated, it reduced interest rates to levels last seen in the Great Depression, pumping immense helium into the emerging housing bubble and failing to rein in exceedingly reckless lending practices (Bubble 2.0).

3. Once that popped, the Fed then resorted to four separate Quantitative Easing (QE) programs, and, after Covid hit, even greater debt monetization; this has inflated almost all asset classes to unprecedented overvaluation, setting the stage for the next crash (Bubble 3.0).

Through these interrelated events, the Fed has waged a nearly 20-year war against interest rates, which have now essentially gone the way of the T-Rex especially on a real basis. It has also continued what was supposed to be a temporary QE program into its second decade. It’s become glaringly apparent to all but the most ardent Fed apologists that it can’t kick the habit of massive stimulus even when the crisis has passed.

Consequently, it has become a serial bubble-blower. If you don’t believe me, just wait (and also, please see Chapter 17 for asset protection strategies). Now, let’s go back and consider the conditions and attitudes that were prevailing after the implosion of the worst of all bubbles, the type that involve the banking system.

In the immediate wake of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) — i.e., the collapse of Bubble 2.0 – the Fed’s shock treatment of fabricating one trillion dollars from its Magical Money Machine (the first quantitative easing or QE), created tremendous suspicion among many investors. It was also a factor behind the Tea Party movement that helped moderate government spending, at least for a few years.

The acute angst over this unprecedented money fabrication also revived the fortunes of a book written years earlier called The Creature from Jekyll Island, a scathing attack on the Fed. It became a business book best-seller, despite sounding like the title to a horror film. Based on what’s transpired since then, perhaps that is an apt analogy and, certainly, in the mind of the author the Fed is a financial monster.

You may have a vague recollection of this purported exposé because it attracted a cult following at the time. This was likely a function of its resonance in those days with the mindset of millions of Americans toward the brazen and presumably highly inflationary action by the Fed with its maiden QE voyage. In fact, nearly two dozen prominent money managers, professors, and economists penned a letter to the Wall Street Journal when QE I was first launched asserting it would surely bring about an inflation disaster.

Here’s an excerpt: “We believe the Federal Reserve’s large-scale asset purchase plan (so-called ‘quantitative easing’) should be reconsidered and discontinued. We do not believe such a plan is necessary or advisable under current circumstances. The planned asset purchases risk currency debasement and inflation, and we do not think they will achieve the Fed’s objective of promoting employment.”

In hindsight, these dignitaries were half right; they whiffed on the inflation call but were right about its infectiveness on the jobless front. It took many years for the unemployment rate to recede back to where it was prior to the GFC.[i]

Around this time, the author of The Creature From Jekyll Island, Edward Griffin, pulled no haymakers when he discussed his views of America’s central bank before a live audience. To wit:

“I came to the conclusion that the Federal Reserve needed to be abolished for seven reasons. I'd like to read them to you now just so that you get an idea of where I'm coming from, as they say. I put these into the most concise phrasing that I can to make them somewhat shocking and maybe you'll remember them.

1. The Federal Reserve is incapable of accomplishing its stated objectives.

2. It is a cartel operating against the public interest.

3. It's the supreme instrument of usury.

4. It generates our most unfair tax.

(To see the rest of Mr. Griffin’s comments, please refer to the Appendix for this chapter.)

Mr. Griffin contended the Fed’s formation needed to be a furtive event because if Congress got wind of their plans to launch America’s first central bank it would have been highly disinclined to pass the authorizing legislation. That part was most likely true, though I find a number of his points listed above to be truth-stretching, to say the least. But here’s his wrap-up:

“Let's summarize. What is the benefit to the members of the partnership? The government benefits because it is able to tax the American people any amount it wishes through a process which the people do not understand called inflation. They don't realize they're being taxed which makes it real handy when you're going for re-election. On the banking side they're able to earn perpetual interest on nothing.

I emphasize the word ‘perpetual’ because remember when the loan is paid back it's turned around and loaned out to somebody else. Once that money is created the object of the bank is to stay ‘loaned up’ as they say. In reality the banks can never stay 100% loaned up and that ratio varies a lot but the objective is to stay loaned up to whatever extent is possible. Generally speaking once this money is created in the loan process it is out there in the economy forever, perpetually earning interest for one of the members of the banking cartel which created that money. There you have in a condensed form, a crash course, on the Federal Reserve System and I can assure you that you know more about the Federal Reserve than you would probably if you enrolled in a four-year course in economics because they don't teach this reality in school.”

The brief groundswell of interest in The Creature from Jekyll Island rather oddly faded away even as the Fed set sail with QEs II, III, and, unofficially, IV. A rational observer would think that such repeated and ineffectual attempts to restore the US economy to its once trendline real growth rate of 3% to 3 ½% would have further enflamed the anti-Fed fires. Yet, except among some of its more dogged critics, such as the aforementioned Jim Grant (a co-signer of the letter to the Wall Street Journal), it didn’t. You might reasonably wonder, why?

In my view, it was one thing and one thing only: a relentlessly rising stock market. Fortunately, for the Fed a bull market is like winning in sports; it’s a wonderful deodorant, as I mentioned in Chapter 12. Similarly, it’s probable that one of the reasons for the popularity of The Creature from Jekyll Island, fleeting as it was, can be attributed to the multi-trillion-dollar hits that people incurred during the GFC. Understandably, they were furious over how much money they’d lost—particularly, those who sold out in terror and missed the screaming rally that came out of the blue on March 9th, 2009.

As previously discussed, it was the suspension of the ill-advised, at least in a panic, mark-to-market rule in March of 2009 that immediately killed the bear and birthed the bull. It was a precursor of what would happen in another March—as in, 2020 — though, in the latter case, at even a more breathtaking speed.

However, as we’ve seen, in the second instance it was the Fed to the rescue, with its radical corporate bond market intervention, not an arcane accounting rule change. And, as I opined at this book’s opening, the Fed could have avoided a tremendous amount of pain — along with over a decade of QEs I, II, III and IV and likely avoiding the need to go into MMT-mode post-Covid — had it used a relatively modest amount of real money (i.e., not printed) to support the credit markets in the fall of 2008. As I’ve observed before, but it bears repeating, one of the smallest interventions the Fed did over the last 20 years was its corporate bond-buying program during Covid and yet it produced a multi-trillion market rally. It was also was a critical factor in causing the short recession in U.S. history.[ii]

Perhaps it was because the Covid crash lasted a mere month that another Jekyll Island-like book wasn’t published in its wake. Or, on a related note, maybe it was because the Fed engaged in such creative and immediate support of markets — such as its coup de grace with corporate debt — that it was spared the kind of withering scorn it received from some quarters after the GFC.

It might have also been due to the fact that, as described in Chapter 2, the Fed’s fingerprints were all over the housing boom — Bubble 2.0 — and the subsequent bust. Conversely, it was impossible to blame the Fed for Covid (I don’t think even Edward Griffin would allege that!). Regardless, it was spared the kind of vilification it received a decade ago. In fact, the increasingly maniacal stock market activity in 2021, especially among the millions of new Reddit and Robinhood “investors”, created a mythical aura around Jay Powell and, even, his three immediate predecessors, as these images reveal.

Figures 1 &2

“Jay Powell: Our Lord and Savior”

Mt. Cashmore

Deification: A fickle phenomenon

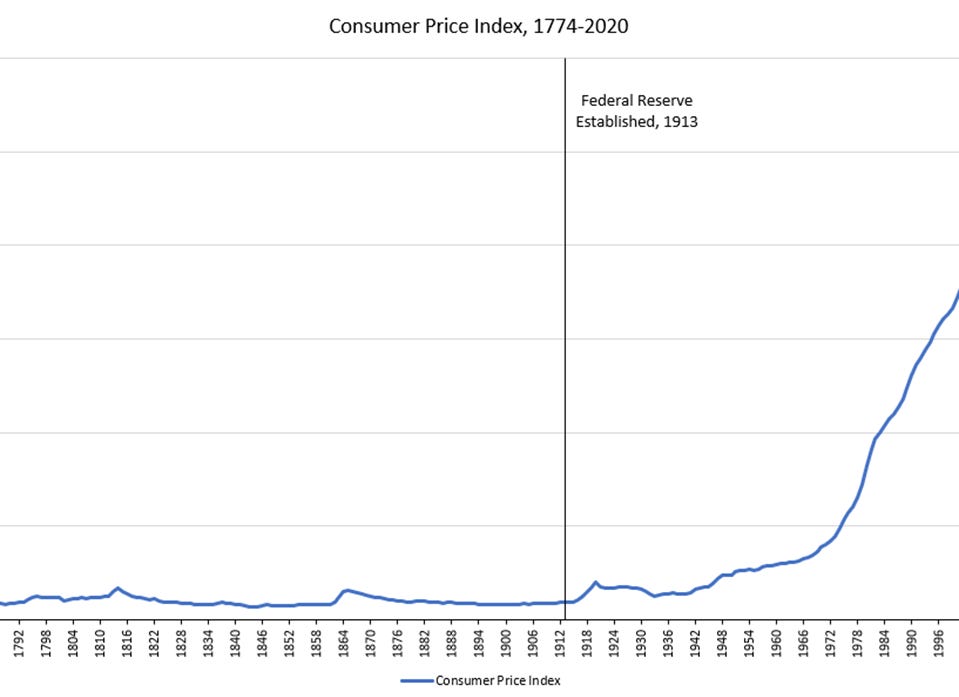

Unfortunately for Mr. Powell (aka, JPOW, to his legions of adoring meme stock-trading fans) his halo began to slip a bit during the summer of 2021. This slippage was caused by Mr. Griffin’s fourth cardinal sin enumerated above — inflation — a scourge he correctly referred to as an “unfair tax”. On that score, the following visual, which is a twist on the one shown in Chapter 6, illustrates the reality of this criticism most clearly.

Figure 3

Somehow, the Fed managed to convince most of America that 2% inflation was desirable. But, as noted earlier, even that modest level caused about a 45% decline in the dollar’s purchasing power over 30 years. And, most bizarrely, the Fed under three of the four chairmen enshrined in Figure 3 above — Ben Bernanke, Janet Yellen and, of course, Lord and Savior Jay Powell — developed an obsession with 2% inflation. Unlike the Maestro (the far-right image on the mythical Mount Rushmore), who had a much more relaxed (and realistic) attitude toward inflation oscillating between 1% and 2%, the other three Fed-heads were determined to keep the CPI at 2%.

In fact, they were willing to expend trillions of dollars the Fed didn’t have to attain what became their elusive “2% Solution”. In the decade after the GFC, it mostly failed in this regard, with the exception of a few truly transitory prints around that magical number. Somehow, 1.7%, or so, simply wasn’t high enough.[iii]

As recently as the summer of 2020, at the Fed’s annual shaker and mover convocation in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, Mr. Powell was begging for higher inflation. Here’s what he had to say:

“Many find it counterintuitive that the Fed would want to push up inflation. After all, low and stable inflation is essential for a well-functioning economy. And we are certainly mindful that higher prices for essential items, such as food, gasoline, and shelter, add to the burdens faced by many families, especially those struggling with lost jobs and incomes.”

The old saying “Pride goeth before the fall” comes to my mind as I reflect on the words by Chairman Powell, and so does another: “Be careful what you wish for; you may get it good and hard.” It’s remarkable that, in such short order, Mr. Powell could go from rooting on higher inflation to becoming among its most prominent victims.

As my one of my favorite sources on financial trends, Mike O’Rourke, Jones Trading’s Chief Market Strategist, wrote in November 2021 about these bizarre comments: “In his attempts to micromanage price stability, Powell created price instability and undermined three decades of stable prices.” Accordingly, this is another example of how quickly long periods of prosperity, stability, and sound policies can be undone by government officials pursuing politically expedient objectives or even seemingly well-meaning goals.

Mike has also brilliantly referred to the Fed’s rinse-wash-repeat modus operandi as “The Afghanistan of Monetary Policy”. The parallels between the U.S. military’s management of the “Good War” and the Fed’s response to Covid are tight, in his view: “In response to a grave crisis, the powers that be responded swiftly and strongly garnering impressive early results. Despite the success, the leadership did not know when or how to end the emergency intervention… Instead, those powers-that-be erred on the side of caution, resulting in greater and greater investment and entrenchment in their policy response. In both scenarios, the frequently flawed Government logic that bigger is better was repeatedly applied.”

Certainly, when it comes to the Fed’s a balance sheet, it has gone big rather than gone home. (Recall that it increases the size of its balance sheet by purchasing bonds with fake money from its Magical Money Machine.) Since the GFC, the Fed’s synthetically acquired holdings have grown by $500 billion per year, an 18% compound rate. This is in comparison to an economy that has grown about 2% per year in real terms or roughly 4% including inflation (nominal GDP). No wonder we had rampant asset price inflation despite a lackluster economy in the 2010s and now, in late 2021, we have a flashback to 1970s-like CPI reports.

As noted at the outset of this chapter, these measures, which we were assured by Ben Bernanke were, in fact, temporary, over a decade ago, have become a permanent fixture. However, their ability to fix anything is highly questionable. In fact, at this point they are likely making a bad inflation situation far worse.[iv]

Yet another irony was that Jay Powell had been beseeching Congress to open the spending--aka, fiscal stimulus--floodgates. He got that one good and hard, too, which is greatly aggravating his inflation problem. The progressive Democratic caucus in Congress and the Biden administration are striving mightily to inject even more trillions of “stim” into an economy that’s already hopped up like the German army was on crystal meth during WWII. (That’s a true factoid, by the way, and, for a time, it fed the myth of the Germanic “super-race”.)

As Gavekal Intelligence Software’s Head of Research, Didier Darcet, has noted, America’s Covid fiscal response has been 30 times the size of the Marshall Plan, in constant dollars. Unfortunately, in this case we didn’t rebuild a war-torn Europe. These staggering outlays have merely been to get our economy a bit ahead of where it was two years ago.

The Fed, of course, has been right up there in the hyper-stimulation department. One quarter of all money created in America’s history came into being in 2020 alone. M2, the primary money supply measure, is at 90% of GDP versus the normal just under 60% ratio. This amounts to over $6 trillion of high-octane money that the Fed has injected in a very short time. Incredibly, despite the “taper” it announced in November of 2021, it was continuing to pump over 100 billion per month into the system at that point. Again, this is all fake money from its… well, you know by now, Magical Money Machine, its very own 3M (not to be confused with the Fortune 100 company known by the same acronym).

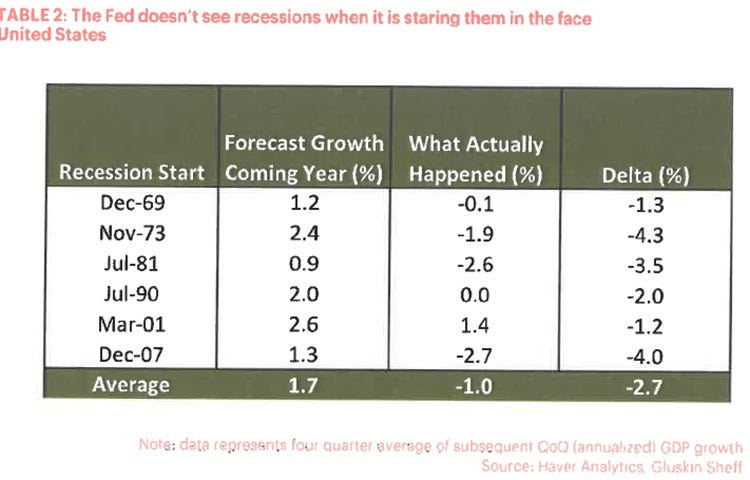

Yet, through most of 2021, the Fed assured the world that the string of shockingly high inflation prints seen early in the year were the now-infamous “transitory”. If this was just an uncharacteristic bad call, that would be excusable. The reality, as I’ve brought up earlier, is that it is standard operating procedure for the Fed. Putting aside its aforementioned inability to forewarn of a single recession, and the monstrous miscalculation it made with regard to the housing market in the early 2000s, it consistently overestimated economic growth through the last decade. It also mis-predicted inflation — back then, on the downside. Again, to me, that was a happy event, but the Fed disagreed… and they’re the ones with the printing press!

Courtesy of data-sleuth extraordinaire David Rosenberg, one of North America’s preeminent economists, over the last decade, which includes 110 major economic datapoints, here’s how “well” the Fed has done in the forecasting department:

On its own fed funds rate, it has been correct 37% of the time.

With what it calls core inflation, 29% of the time.

On the unemployment rate, 24% of the time.

Regarding real GDP, 17% of the time.

Clearly, the Fed needs to spend some of its enormous budget on a dart board. Based on the fact that the Fed sets the fed funds rate (hence the name) that one strikes me as particularly pathetic.

David also created the following table showing its forecasting track record around the time of the last six recessions prior to Covid. (In the case of March 2001, the recession started before then, but the Fed missed that one, too.) This takes either some really bad luck or, perhaps, an extreme inability to call a spade a spade. Figure 4

Complicity or duplicity?

While the above is embarrassing and confidence-shaking--especially, for an institution to which politicians continue to grant ever higher levels of responsibility--what I’m going to cover is far worse. It concerns the Fed’s credibility and, frankly, its honesty.

Yes, I know those are harsh words (though not quite Edward Griffin harsh) but let’s consider the evidence. First off, there is the Fed’s preferred measure of market valuation, what it calls the equity risk premium. Don’t worry — it’s not as esoteric as it sounds. What it does is compare the prevailing yield on long-term treasury bonds to the earnings yield of the stock market. While I’ve covered this before, it’s worth a recap: If the P/E on the S&P 500 is 25 then the earnings yield is 4% (if, as in days of yore, the P/E was 10 the earnings yield would be 10%, an admittedly easier calculation). As I’ve mentioned before, an earnings yield in the stock market is like a “cap rate” in real estate.

The Fed has repeatedly batted away concerns that the stock market is in another bubble by pointing out that the earnings yield is much higher than the interest rate on long-term treasuries. Here’s a typical response to a reporter’s question about overheated market conditions from Lord and Savior Jay Powell, as the mania in meme stocks was raging in early February of 2021: “If you look at P/Es, they’re historically high, but, you know, in a world where the—where the risk-free rate is sustain—is going to be low for a sustained period, the equity premium, which is really the reward you get for taking equity risk, would be what you’d look at. And that’s not at, at incredibly low levels, which would mean they’re not overpriced in that sense.”

Considering that this is Chapter 16 of this book, I’m confident readers can detect a slight flaw in this logic: the risk-free rate, as in the treasury interest rate or the fed funds rate, is set, or at least manipulated, by the Fed! In days gone by, it only controlled the fed funds, or overnight, rate, but, in the wake of more than a decade of repetitive QEs, it also exerts considerable control over longer term interest rates. After all, the roughly $8 trillion of pseudo-money it has whipped up from its MMM since the Global Financial Crisis has primarily gone into treasury bonds. Thus, the Fed doesn’t just have its thumb on the scales, it’s leaning on one side with the full weight of its printing press.

Wait, it gets worse. Later in the same press conference, Mr. Powell threw out this line: “So if you look at what’s really been driving asset prices really in the last couple of months, it isn’t monetary policies. It’s been expectations about vaccines.” His last point is a fair one, except that he uttered these words during the previously mentioned meme-stock insanity that saw GameStop, AMC Entertainment, and BlackBerry ripping 2,385%, 842% and up 326%, respectively in a few weeks, along with a litany of other lottery-ticket stocks that experienced moonshot trajectories. To believe that type of hyper-speculative behavior was a result of vaccines, rather than trillions of free money sloshing through markets, is either extremely naïve or exceedingly disingenuous.

But here’s the real clincher — a few sentences later he had the chutzpah to say: “And I think, you know, I think that the connection between low interest rates and asset values is probably something that’s not as tight as people think, because a lot of different factors are driving asset prices at any given time.”

Really? Just a few minutes earlier, Jay, you dismissed fears that this is one of the biggest equity bubbles of all-time, which this author absolutely believes to be the case, by saying prices are justified by low rates (that you created). And then you say it’s not as tight a connection as people think? Oy vey, this is some serious double-talk, even for a politician, which the head of the Fed has clearly become.

There have also been some serious contradictory utterances by Mr. Powell when it comes to what has obviously become the Fed’s number one priority, the unemployment rate. In a July 2021, “presser” he stated that the jobs market was “some ways off from substantial further progress.” Then, a few minutes later, “we’re clearly on a path to a very strong labor market with high participation, low unemployment, wages moving up across the spectrum. That’s the path we’re on and it shouldn’t take long.”

He was right, it didn’t take long. Despite the Delta Variant’s drag on the U.S. economy through the summer of ’21, by October there were a remarkable 500,000 new jobs created. The unemployment rate fell to 5.9% by 6/30/21, 5.1% by 9/30/21, then to 4.2% by 12/31/21%. Coming out of the Great Recession, it took over five years to get down to 5 ½% jobless rate. Lower joblessness is wonderful but when “we’re clearly on a path to a very strong labor market” and the Fed continues to maintain deeply negative real interest rates, as well as maintaining money manufacturing at a $120 billion monthly rate, an inflation problem is almost a certainty. And, sure enough, as summer turned into fall, the world—and, even, the Fed--began to realize that inflation was not exiting stage left anytime soon. Workers started waking up to the disquieting reality that despite hefty pay increases they were often losing ground to a CPI that was outrunning their raises.

It was more of the same at Mr. Powell’s November 2021 “meet the press” event. Here’s what he said: “If we do conclude it’s necessary to do so (raise rates), we will be patient, but we won’t hesitate.” The Fed is supposed to ooze credibility and gravitas but statements such as that non-sequitur move in exactly the wrong direction.

In a November 2021 Washington Post Op-Ed, former Obama administration Treasury Secretary Larry Summers pointed out that in Mr. Powell’s August 2021 Jackson Hole speech (again, this is one of the Fed’s most important gatherings), he made a “comprehensive and authoritative statement”. It was based on five pillars ranging from his belief that inflation was limited to a few sectors to citing global deflationary trends still being in place. As Mr. Summers methodically addressed, all five turned out to be disproven by subsequent developments.

However, possibly the worst example of the Fed’s increasingly fast and loose relationship with the truth might be related to that highly charged acronym, MMT. First, for those who doubt America is actually engaged in this once fringe economic model, consider the views of billionaire investor Howard Marks, co-founder of Oaktree as far back as 2020, when MMT was in the early stages of policy implementation: “Possibly without serious vetting and a conscious decision to adopt it, Modern Monetary Theory is here. Whether we like it or not, we’ll get to see its impact much quicker than I thought.”

Like Howard Marks, I thought MMT was coming, but not nearly this soon. For sure, Covid brought on a full-blow version but, as I noted earlier, a stealth version began as early as September 2019. Thus, it started under the Trump administration, but it hit a crescendo in 2021 under the Biden administration and its repetitive multi-trillion spending programs.

Because, as I explained earlier in this book, there is no way the bond market can absorb all of this supply--unless rates were freely set by profit-seeking investors at much, much higher rates--the Fed has to fill the role as primary buyer. This is what is known as debt monetization and, hence, de facto MMT.

When MMT was attracting considerable media attention in 2019, two Fed economists stridently warned CNBC of its dangers. They correctly observed that history has taught such policies lead to high, even hyper-inflation and economic ruin. Yet, U.S. policymakers not only resorted to MMT during the worst of the virus crisis they have maintained it even as the U.S. economy gathered significant momentum.

In fact, Chairman Powell himself in early 2019 denounced MMT as “just plain wrong”. If it was wrong in 2019, why did the Fed do $5 trillion of it from 2020 through 2021?

Despite the observations of heavyweights like Howard Marks that MMT is the economic order of the day, there are those who say it’s not really happening. But, as I alluded to early in this book, the most high-profile advocate of MMT, Stephanie Kelton, Bernie Sanders economic advisor in his 2016 presidential campaign, has said the U.S. is behaving in a “more MMT way”, as she told Barron’s in July 2020. Since then, of course, it’s been acting in way, way more of an MMT way.

Interestingly, as even MMT advocates like Ms. Kelton have conceded, you keep pressing the “More” button until inflation shows up. Well, that certainly happened in 2021 and yet what has been the Fed’s reaction function? Just like the old Saturday Night Live skit with Christopher Walken: “More cowbell!”. In other words, for an economic theory the Fed not long ago held in disrepute, it certainly became an avowed convert and an even more enthusiastic practitioner.

While it’s fashionable these days to turn a blind eye toward MMT and its escalating threats to our nation’s finances, if not its very existence, I refuse to cave into that reckless mindset. This MMT implementation is going to end not just in tears but in anguished sobs, at least for those who don’t recognize it for what it is and prepare accordingly.

Arguably, the finest Fed chairman in its history was Paul Volcker, the great inflation slayer. Long ago, he uttered some words this Fed would be well advised upon which to seriously reflect. “The truly unique power of a central bank, after all, is the power to create money, and ultimately the power to create is the power to destroy.” There is no doubt in my mind Mr. Volcker would believe the institution whose reputation he once rescued is now employing a highly destructive power.

Yet, back on the dissembling topic, Mr. Powell has repeatedly assured us that should inflation become an issue he is prepared to act. As of late 2021 that action, thus far, amounted to the slightest dialing back of the easiest monetary conditions in American history. The reality is that, at this time, the Fed continues to be in the most extreme stimulus mode in which it has ever engaged, other than a few months back. How that squares with anything remotely related to inflation vigilance is a question that perhaps only Mr. Powell--who has repeatedly proven he can maintain two contradictory thoughts simultaneously--can attempt to answer.

What we are witnessing is a gain-of-function, monetary policy style. In virology, this refers to researchers doing experiments to make a pathogen more contagious and, potentially, more virulent. The Fed’s great experiment with trillions of dollars of debt monetization is already proving to be extremely infectious and increasingly harmful.

Once the dark side of its MMT investigative trial has emerged, the Fed’s predicament became glaringly apparent. David Rosenberg estimated that based on its nearly $9 trillion dollar balance sheet (again, nearly all acquired via its Magical Money Machine), the effective fed funds rate was minus 10%. That number might be overstating how deeply negative its key interest rate was, but it was likely in the general vicinity of accurate.

Figure 5

Even if the de facto fed funds rate was minus seven or eight percent with the CPI running around 5% (and probably higher) in late 2021, the Fed is at least 12% behind inflation. The amount of tightening it needed to do at that point to merely catch up to the CPI was staggering and, in early 2022, it still is. To sell assets (equivalent to rate hikes) and actual fed funds increases to that extent is almost certain to incite a financial market riot.

Accordingly, the Fed faces two stark choices: Remain massively behind the CPI by keeping real yields severely negative, further stoking inflation, or tighten like mad and pray markets don’t collapse. It’s my personal belief--which might be proven dead wrong by the time you read this--is it will choose door number one. As I’ve observed before, the Fed has printed itself into a very tight corner. (As a February 2022 update on this uber-essential topic, Powell & Co is preparing to raise interest rates—finally!—and also begin letting its Michelin Man-like balance slowly shrink. It remains my view it has no chance of tightening anywhere near enough to control the inflation it has unleased.)

However, don’t expect Mr. Powell or the Fed to admit the disaster they’ve created. As the Wall Street Journal wryly commented in its July 29th, 2021 column: “One trait of the modern Fed is never to take responsibility for financial and economic problems.” Certainly, as noted at the outset of this chapter, the pandemic was not the Fed’s fault; however, enormously overstimulating the economy, even as inflation surged, definitely falls at its doorstep.

As I wrote at the outset of this chapter, it's not my intention to allege that Mr. Powell is an evil man who intentionally wants to harm the American economy. Far from it and, in fact, I initially had high hopes he would reverse the perma-easy policies that began under Ben Bernanke and continued with Janet Yellen. It’s my belief he’s been trapped by circumstances. His inability to fully execute a proper tightening cycle in 2018 despite the robust economy he inherited when he took the helm early that year was reflective of that reality. Sadly, I think he’ll go down as the fall guy for policies that his predecessors started, similar to Arthur Burns in the 1970s.

Frankly, being head of the Fed has become an impossible and thankless job. When someone asked Jim Grant, one of our central bank’s most persistent, if affable, critics what he would do if he was made chairman of the Fed, he didn’t miss a beat: “Resign”.

[i] A related economic datapoint is that the “output gap”, which measures excess capacity, like unemployment and idle factories, never quite fully closed during the 11-year expansion that ended with Covid. However, in less than two years since the onset of the pandemic recession the output gap has already been eliminated.

[ii] Let me clarify and emphasize the Fed should never have put itself in a situation where it needed to resort to this type of market manipulation; however, what was done, was done, and at that point, as in 2008, it was the least bad option.

[iii] To my simplistic mind, 1% inflation is twice as good as 2% inflation, not vice versa.

[iv] Ironically, the Fed may have made a serious unforced error by focusing on the wrong CPI measure. The New York Fed long ago created a price increase-tracking metric called the “underlying inflation gauge” or UIG. It is meant to monitor “stickier” or more persistent inflation trends. Based on the UIG, there were only about 3 ½ years out of the past decade when price increases fell below the 2% level the Fed is so fanatical about maintaining (at least when they’re running below that level; apparently, it is not as uptight when above they are above, even way above, like in 2021). By the way, the NY Fed’s sticky inflation gauge was running at a record high of 4.3% as 2021 wound down. (The UIG factoids are courtesy of Barron’s in its 11/15/2021 edition.)