Every Investor’s Favorite Bubble

Chapter 14

Let’s get real… about our returns

Who doesn’t love a raging bull market? Especially one that just keeps romping and stomping, aside from some brief stumbles when an out of the blue shock comes along. Because I’ve been in the investment business longer than a lot of today’s analysts, traders and portfolio managers have been alive, I can personally attest that bull markets are much more fun than bear markets.

On that point, this bull has been running for so long that many financial professionals have never seen a deep and lasting bear market. The same is true with today’s new crop of investors, millions of whom have only seriously become involved with stocks since the pandemic. But an organization with serious Street cred (as in Wall Street credibility) has some sobering news for the market newbies.

Among investment firms with the best long-term asset class return forecasting records is Boston-based Grantham Mayo Otterloo (GMO), which manages nearly $64 billion on behalf of its clients. As the S&P has steadily risen from undervalued back in 2009, to fairly valued by 2012, to heroically priced in 2014, then to extraordinarily pricey by the summer of this 2018, and, ultimately, egregiously overvalued by the fall of 2021, GMO has methodically lowered their return expectations over the next seven years.

Figure 1

As you can see, what they are projecting is anything but fruitful. Essentially, with a 50/50 mix of U.S. stocks and bonds, GMO is looking for around a 5% average annual negative return, inclusive of inflation. Even though these are real or after-inflation numbers, the implications are enormous if they’re right. This is particularly true for the tens of millions of Baby Boomers who need to live on the fruits of their portfolios. (It is fair to note that GMO has been projecting poor returns for the last eight or nine

years. Yet, as noted, they have increasingly marked down those future numbers as U.S. stocks have continued to push higher. Their long-term track record argues in favor of expecting them to be right at some point with more color on when that might be to follow.)

One of Warren Buffett’s classic adages, “Be fearful when others are greedy and greedy when others are fearful” is predicated upon a crucial and rather obvious notion: you need to have cash on-hand to capitalize on others’ fears. But all too often, people become complacent during boom times and allow their capital to remain in investment sectors, areas, or asset classes that are way beyond their sell-by date. Moreover, there is a strong and highly destructive tendency to move funds from underperforming vehicles into the hottest areas which then sets the stage for actual losses once the skyrocketing sector, style, or stock inevitably succumbs to the laws of gravity.

If there is a devil-like being at work in the financial world, one of his nastiest tricks is making the most dangerous (i.e., grossly overpriced) asset classes look irresistibly attractive. Often, these slices of the investment universe have been generating outrageous returns for several years. The action in tech stocks back in the late 1990s was a graphic, though long ago, example of this.

More recently, it has been the relentless rise in the S&P 500, with but a single down year since 2009. Thus, it’s been almost 13 years of a singular bull market, if one ignores the slight negative print for 2018 and the Covid catalyzed flash-crash. This also excludes some less serious gut-checks like early 2016.

There is simply no question this has been one of the most spectacular bull markets in U.S. history, going all the way back to when stocks were traded under the Buttonwood Tree in New York’s nascent financial district. (It must have been quite a challenge to keep all the birds on the tree limbs from leaving their own marks on the cash and stock certificates.)

Figure 2

This bull rampage is right up there with the 1920s and the 1982 to early 2000 mega-runs. (It’s also fair to note what happened in the wake of those was a mammoth give-back of what looked to be permanently accrued profits; again, more on that shortly.)

Bull markets, especially when they are particularly powerful and/or long-lasting, create a situation where investors become afraid to sell. We humans have been programmed over the eons to pursue activities which provide an immediate reward and avoid those that produce near-term pain or disappointment. That reality has helped us survive endless adversities (that we keep voting for our feckless politicians would seem to be an exception to this rule). It goes against every helix of our DNA to pull out of an activity that’s earning money even when wisenheimers like this author trot out a copious collection of charts and graphs to show that the S&P 500 is dangerously inflated (those shall be soon forthcoming).

Thus, in a way, late-stage bull markets become like an elaborate con job. Perhaps some older readers might recall the entertaining film from the early 1970s, starring Paul Newman and Robert Redford, The Sting. Messrs. Newman and Redford portrayed thoroughly likable conmen who come up with an elaborate scheme to bilk a rich crime boss, played by Robert Shaw. The key to making their ploy work was to let “the mark” win. Once he’d scored a bunch of easy money, he was ripe for the plucking.

And so it goes with investors. When we’re sitting on years and years of double-digit gains, we become convinced that: A) the market is safe and B) the high returns will continue. In these situations, investors act as though the lavish profits they’ve “earned” in recent years are somehow securely tucked away, as in a bank. They lose sight of the historical fact that returns during late-stage bull markets are about as lasting as a politician’s campaign promises. In reality, those gains tend to be wiped away almost overnight and the more inflated the market has become, the more years of “in the bank” gains are suddenly repossessed.

However, in an era where there have been tens of trillions of central bank funny money created around the world, bear markets seem to have gone the way of the dodo bird, particularly in the U.S. This has made it very tough on folks like those at GMO who believe one of the few constants in the financial markets is reversion to the mean. (It’s also been challenging for this author though, fortunately, Evergreen has pounced on the brief downdrafts seen since this bull’s birth in 2009, particularly the Covid crash.)

Flash crash flashbacks

As noted in earlier Bubble 3.0 chapters, the 1987 crash was the first time that computers played a starring role in a major market collapse. Since then, of course, we’ve seen a number of those computer-driven cliff dives, although they’ve been limited to, thus far, the “flash crash” variety. These “now-you-see-them, now-you-don’t” panics happened in 2010, 2011, 2015, 2016, 2018 and, of course, 2020.

In some cases, there were some remarkable buying opportunities — if an investor moved at hypersonic speed. For instance, in August 2015, one ironically classified “low-volatility” ETF plunged 43% in less than an hour!!! More recently, another highly defensive equity security, the iShares Preferred and Income Securities ETF, fell 40% in four weeks, from late February to late March

of 2020, with most of the plunge happening between March 16th and 23rd. These types of moves in conservative issues simply should not happen were markets truly efficient.

Today, as we all know, or at least we should, computer- or algorithm-based trading is dominant to a far greater degree than it was in 1987. Estimates are that these now represent 80% to 90% of New York Stock Exchange volumes, though that seems high to me. What is less well understood is that these systems generally don’t try to anticipate the future, as financial markets typically have in the past.

For example, if certain words in Fed press releases have led to market rallies, the same relationship is projected by the machines to happen again. One fascinating factoid in this regard is how much more the market has risen, like 80% of all returns, on Fed press conference days (even if those brought rate hikes) than it has the rest of the time. But don’t ask me to explain why. My only insight is that it simply shows that perhaps the only force driving the stock market these days that is more powerful than the “algos” and computers is the Fed.

Figure 3

Source: Liberty Street Economics as of 11/26/2018

This is definitely not how markets formerly behaved. As the celebrated economist Paul Samuelson once quipped, the stock market at one time had discounted nine of the last five recessions. In my opinion, the enormity of this shift has not been even close to fully appreciated. Most investors seem to believe the market’s discounting mechanism is largely unchanged.

Yet, as my astute partner Louis Gave has repeatedly pointed out, this is decidedly not the case. Rather than a market driven by myriad individuals spending endless hours analyzing economic, corporate, and geopolitical information, most of the movements these days are caused by the way in which computers react to current news events. This is not to say research isn’t still conducted but rather that it is overwhelmed by computerized-trading and, of course, the trillions of dollars that have shifted from actively managed vehicles into index funds.

The passive investing bubble

It’s common knowledge that the active investing community has been losing hundreds of billions, if not trillions, to its passive counterparts over the past fifteen years. The chart below makes that abundantly clear.

Figure 4

By definition, there is no research performed by these index-type vehicles. In the “good old days”, the assumption was this was not a problem since markets were dominated by active managers who performed intensive analysis. The relatively limited number of passive players back then were effectively coattail riders and minimally impacted prices. This was the cornerstone of the efficient market hypothesis (EMH) which, in turn, was, and still is, the essential assumption of passive investing. Even in bygone days, markets would become highly inefficient during bubbles and anti-bubbles (i.e., panics.) This is a key reason why stock prices have always been more volatile than underlying fundamentals would indicate.

But think deeply about current conditions in this regard. Active managers are no longer the elephants, they are the fleas. The monster pachyderms today are computers and passive funds. In other words, most money now is pushed around by entities that are not conducting much forward-looking research, if any at all. If that doesn’t raise red flags in your mind, you are way too invested — literally — in the current “don’t worry, be happy” mindset of the moment.

There is a significant upside to this situation, however…at least for independently minded and research- driven investors. Because indexing is so brainless–constantly making expensive stocks more expensive and cheap ones cheaper – even in a market as hyper-valued as late 2021 and early 2022 there were bargains. Some were even of an extraordinary nature. This was particularly the case after the severe damage that was done to a multitude of stocks since the fall of 2021, despite that the overall market was close to record highs in early 2022.

This fits within one of my main themes of a “Great Rotation” now under way toward value stocks and away from growth issues that have been the dynamos of the last fifteen years. As they say, especially with such divergent valuations across sectors, it’s a market of stocks, not a stock market.

Money manager Seth Klarman has one of the finest track records in the investment business and he’s definitely a thinking investor. He’s been able to generate stellar returns despite the difficulty of besting passive vehicles (which are always fully invested) in a seemingly immortal bull market.

Here’s what he has to say about the dangers of this phenomenon: “When money flows into an index fund or index-related ETF, the manager generally buys into the securities in a proportion to their current market capitalization… thus today’s high-multiple companies are likely to also be tomorrow’s, regardless of merit, with less capital in the hands of active managers to potentially correct any mispricings.”

He went on to observe: “Stocks outside the indices may be cast adrift, no longer attached to the valuation grid but increasingly off of it. This should give long-term value investors a distinct advantage. The inherent irony of the efficient market theory is that the more people believe in it and correspondingly shun active management, the more inefficient the market is likely to become.” (Emphasis mine)

This reality may be why there has become such a disconnect between an America that seems to be unraveling and financial markets that are behaving like times are about the best they’ve ever been – with a massive assist, of course, from the Fed’s Magical Money Machine. As long as trillions of new liquidity are being created, the computers and passive vehicles couldn’t care less about underlying fundamentals.

For years and years, this paradigm has been investment nirvana, at least for all those who went with the flow. The algorithm-driven computers have almost exclusively been on the buy-side due to things like serial quantitative easings (QEs, now escalated to MMT, per Chapter 6), massive and deficit-financed corporate tax cuts, mostly rising earnings (especially in the U.S.), the highest profit margins in history (again, in the U.S.), and, most important of all, zero, and even negative, interest rates that made nearly every risk-asset (like stocks) look irresistible.

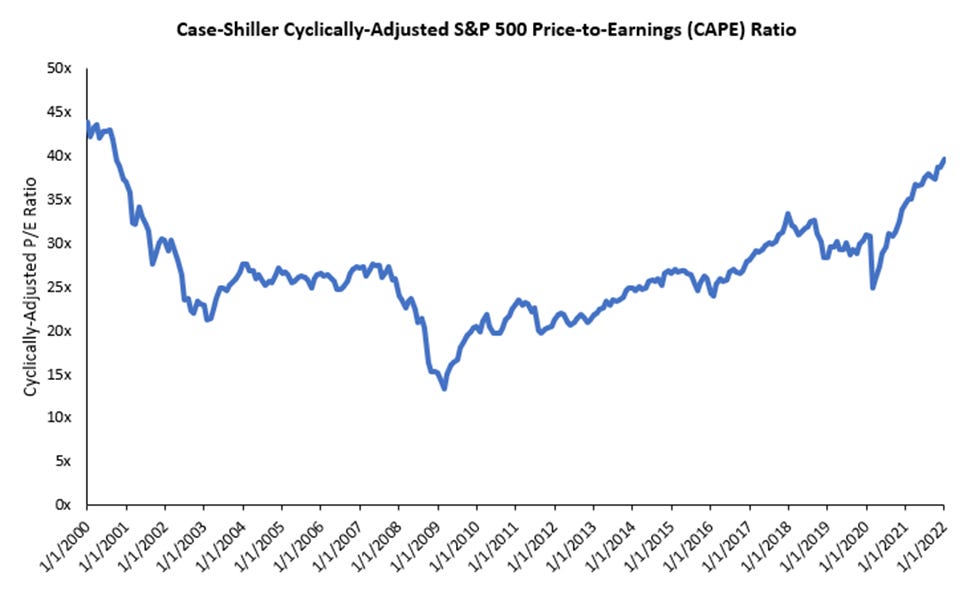

CAPE fear

For decades, one of the best warnings of stock market trouble was the so-called Shiller P/E. It is the brainchild of famed Yale professor Robert Shiller, who also created the Case-Shiller Housing Index. Like me, Prof. Shiller issued advanced warnings of both the tech and housing bubbles (and, like me, he was largely ignored… until after the fact). His metric is also referred to as the Cyclical-Adjusted P/E (CAPE) which is more descriptive. As it sounds, it seeks to smooth out earnings over a ten-year timeframe and, further, it adjusts them for inflation.

The cyclical adjustment is critically important, in my view. For example, if you didn’t do this you would have stayed away from stocks in 2009, at the bottom, because earnings had collapsed. Consequently, at that point, the unadjusted, or unsmoothed, P/E was very high. The reverse is true late in an economic up-cycle when profit margins are near peaks. As you can see below the CAPE gave solid buy signals in 2003, early 2009, and during the Covid crash.

Figure 5

In decades past, the CAPE actually got much lower during bear markets than in 2009 or March 2020. There has clearly been a major upward shift in valuations that has happened over the last 30 years. The long decline by interest rates has undoubtedly been one crucial factor in that regard. But my great friend Vincent Deluard, chief strategist at StoneX, has discovered another influence at work.

He divided the last 140 years of U.S. stock market history into two sections: one being the 112 years prior to the creation of the S&P 500 index ETF (SPY) and the nearly 30 years after that with one decade carved out. As you can see in the following two charts, there has been an obvious trend change to the upside. Said differently, the prior reversion to static mean, or average, tendencies no longer exist. (Note:

Vincent left a gap in his charts from 1993 to 2003 because he felt that period was a transition phase from the former active investor dominated era to that of passive dominance. I have added a chart that shows the CAPE continuously from and, as you can see, on this basis the U.S. stock market is more highly valued than it was in 1929, though not quite as insane as 1999.)

Figure 6

Source: Shiller

As bad as the above portends for future U.S. equity returns, it’s actually worse when you dig deeper. Profit margins are exceptionally elevated for publicly traded corporate America. While they’ve been in rarified territory for an unusually long time, there are changes afoot. Typically, margins are highly mean reverting. In a freely operating capitalistic system, it’s exceedingly hard to maintain fat profit margins because they nearly always attract intense competition.

Certainly, as noted earlier, companies with unusual barriers to entry — like the mega-cap names such as Microsoft, Amazon, Google, Facebook, et al — qualify as exceptions to the usual profit cannibalization which capitalism generally ensures. (This assumes markets and economic actors are allowed to do their competitive thing).

In the case of the “FAANGM” stocks, the so-called “network effect” makes stealing away their customers with lower prices extremely challenging. But even for this elite cohort, the future looks less hospitable. Political and regulatory pressure is rapidly mounting. China is a graphic illustration of what can happen to big tech companies when their own government turns on them.

For corporate America overall, the threats to structurally high profitability are accumulating. One obvious change is inflation. While some companies have been able to easily pass on price increases to offset soaring input costs, many were not so fortunate as inflation erupted in 2021, despite the Fed’s repeated assurances that it was transitory. FedEx and Kimberly-Clark were two blue-chip examples of impaired earnings because of costs rising faster than sales.

Closely related to this, employee compensation began to heat up as 2021 progressed. Labor shortages became so acute that employers were offering lavish inducements with behemoths like Amazon offering $3000 “signing bonuses”, up to $22 per hour pay, and free college education to new hires. The following image (taken by this author at an Exxon gas station in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, over the summer of 2021) reveals the extreme labor shortage at the time. Though an anecdote, it was one of countless along these lines that almost all of us have repeatedly seen in recent years.

Figure 7

Since labor is almost always the largest corporate expense item, this is a powerful threat to profit margins. Thus, it’s difficult to envision they will stay at the levels seen below.

Veteran money manager John Hussman has pioneered a way to adjust the CAPE for variable profit margins. Appropriately enough, he has dubbed it the Hussman Margin-Adjusted P/E (MAPE). Interestingly, during the late 1990s boom, margins were not that stretched—certainly not to the degree they were for much of the 2000-teens. As you can see, using his methodology, the U.S. stock market took out the 1999 peak early in 2021. Because of the hefty appreciation throughout the year, the Hussman MAPE rose even further into the ionosphere.

Figure 8

A market commentator could rationally argue that record profit margins deserve a lower P/E, not a higher multiple, since the odds are high of an eventual plunge in margins below normal, as occurs during recessions. Of course, if one believes that margins have hit a permanently higher plateau, it’s a different,

more bullish, story. History would indicate that’s unlikely and, based on the aforementioned threats to profits, I’d argue it’s best to side with historical precedents. But, obviously, based on the shockingly high

valuations that have prevailed for so long, the market is oblivious to the obvious.

As my good friend and fellow financial newsletter scribe Jesse Felder emailed me in September 2021: “The problem I have with PE ratios is that in order to use them you have to make the assumption that profit margins will remain steady indefinitely into the future. In other words, when profit margins are high (as they are today — record high, in fact) the PE ratio is suppressed to a degree… Jeremy Grantham has called margins ‘the most mean-reverting series in finance’. They haven’t mean-reverted for the past couple of decades but that doesn’t mean they won’t going forward. To the extent they do, current PE ratios will understate the risk valuations currently present to investors.”

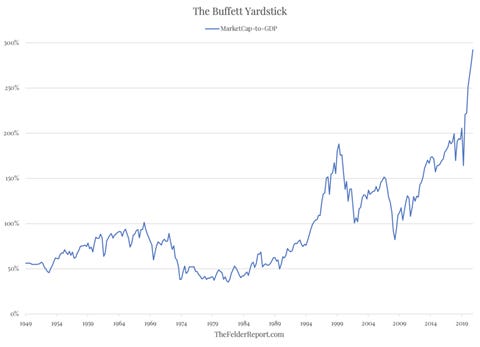

This gets back to the increasingly powerful influence of passive, research-free investors. As Vincent Deluard rightly observes, index funds are price insensitive. In other words, when the money comes in, it needs to get deployed, regardless of how inflated prices might be versus historical measures like P/Es, price-to-sales, and the overall market value relative to the size of the economy (often referred to as the Buffett indicator, per Figure 9 below).

At a time when trillions upon trillions of fake money — that “pseudough” I mentioned earlier – are created on a yearly basis, the torrent of dollars into stocks has become overwhelming. This is a source of price insensitive demand never seen before. As described in Chapter 1, the staid Swiss National Bank has even printed money to directly buy U.S. stocks. In other words, it hasn’t made any pretenses as has the Fed and the ECB about only buying bonds and leaving it up to market participants to redirect the proceeds of their binge-prints into equities.

This effect has only reinforced the natural trend-following instincts of retail investors. After years of being largely disinterested in stocks (at least since the late 1990s tech orgy), Mr. and Mrs. America are buying stocks like never before; meanwhile, globally it’s the same story. In fact, this tsunami of new money has been so extreme that the annualized inflow for the first half of 2021 was greater than for the prior 20 years combined!

Figure 9

10/27 WSJ

Consequently, it’s the same old value-destroying story of retail investors buying the most at the top, as I’ve chronicled in earlier chapters.[i] One could certainly challenge the “at the top” phrase, but when you see the kind of visuals displayed below, it’s fair to say we have to be at least in the zip code of Tarsus Terminus. Similarly, U.S. households have 36% of their net worth in stocks, materially higher than the 32% seen during 1999 and early 2000, what was the biggest stock market bubble in American history. BofA Chief Investment Strategist Michael Harnett stated in September 2021 that his firm’s high net worth clients were 65% in stocks, the highest ever.

Figure 10

Potential pinpricks in waiting

It takes a healthy dose of denial not to concede that at some point the downside reversal is nearly certain to be cataclysmic. Yet, in fairness, as you can easily see from the three images above, the U.S. stock market has been in the valuation danger zone for years. Why should that change anytime soon?

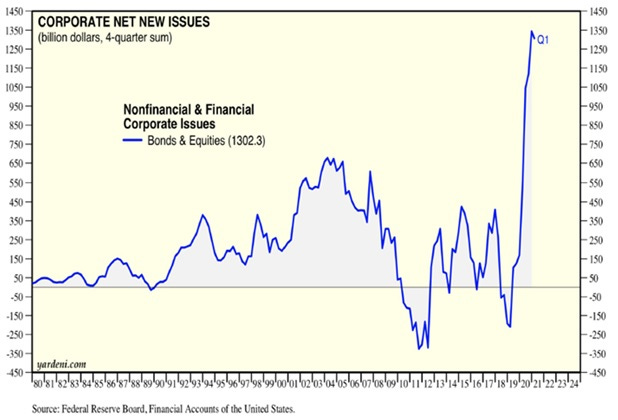

One potential “valuation restoration” factor might well be supply. Unlike for nearly all of the bull market that began in March 2009, there is now a glut of initial public offerings (IPOs), as you can see below.

Figure 11

Another source of supply is coming from corporate insiders. As shown in Figure 12, courtesy of the author of Quill Intelligence and a frequent CNBC guest, Danielle DiMartino Booth, insiders sales relative to buys have rocketed to a level far above anything seen during the giddiest years of the great bull market of the past dozen years.

Figure 12

In reality, insider dispositions don’t create much in the way of supply. However, when the number of sellers swamps those on the buy side to the degree seen above, it’s a strong signal by those who know their companies the best… and, clearly, it isn’t a bullish one. After all, as others have noted, there

are many reasons why an insider might sell her or his own shares but believing the share price is undervalued isn’t one of them. This was another profound “tell” that the U.S. stock market was exceptionally expensive in late 2021.

Next, there is a growing threat on the demand side. As noted in Chapter 13 on buybacks, these have been an extraordinary source of market ballast. Buried within the Build Back Better legislation being wrangled over in Congress as I write these words is a 1% tax on share repurchases. Its fate is unknown at this time but it does show the swelling antipathy toward repurchases by U.S. policymakers, as chronicled in more detail in Chapter 12.

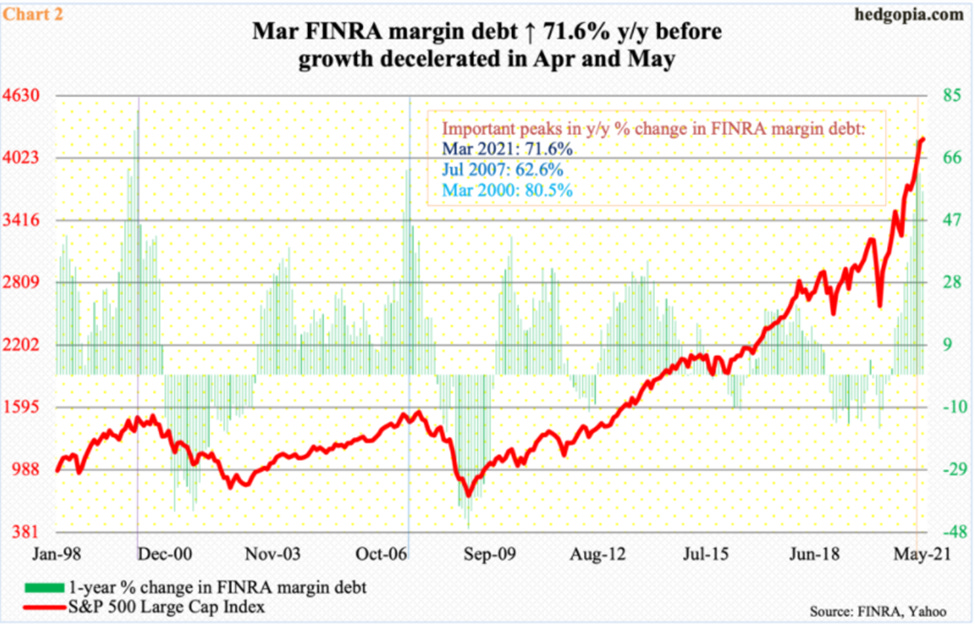

Leverage is, of course, an additional, though very fickle, source of demand. In the case of the stock market, when margin debt is increasing, there is incremental buying power being created. As in all late-stage bull markets, margin debt has risen to dangerous heights. As you can see in the following visual from my Katmandu-based friend Paban Pandey, this is no stock market version of Shangri-La. The growth rate for margin debt on a year-over-year basis was about 72%, a pace only exceeded during the wild blowoff in the terminal stages of the late, not-so-great tech bubble. You might say stock market leverage became Himalayan.

Figure 13

Source From Hedgopia

When deleveraging sets in, as it inevitably does, this quickly morphs from a source of demand to a source of supply. For contrarians with cash on hand, the forced liquidation that accompanies what are essentially massive margin calls are fantastic buying opportunities. For the millions of investors who are far out over their skis with leverage, these reckonings are catastrophic. It’s highly improbable this time will be different.

The late Barton Biggs, for many years Morgan Stanley’s Chief Strategist (and one of the few to give an advance warning of the tech wreck), once quipped: “A bull market is like sex. It feels best just before it ends.” For millions of retail investors, it hasn’t felt this good since… well… that would be the tech bubble. That’s the last time they were so engaged with stocks and making such immense sums of easy money.

Super-investor, financial author and Wall Street Journal columnist Andy Kessler gave some cogent clues in his WSJ “Inside View” Op-Ed on March 8, 2021 as to, in his words, “When the Boom turns to Bust”. To wit: “How do these bull bashes end? When the last skeptical buyer finally sees the light and buys into the dream that every car will be electric, that crypto replaces gold and banks, that we overindulge on vertically farmed ‘plant-based steaks’ while streaming ‘Bridgerton’ Season 5 before we hop on an air taxi for Mars. Those last skeptics (maybe already) convince themselves there’s no longer any downside. And then boom, it’s over.”

When you see cover stories like this from Barron’s, the WSJ’s sister publication, rationalizing meme mania, one has to suspect that “And then boom, it’s over” is nigh at hand. Furthermore, when two-thirds of all the companies in the Russell 3000 Growth Index are losing money, that’s another alarm bell going off that peak nuttiness might be around the corner… or at least in the neighborhood.

Figure 14

Figure 15

Yet, the demise of a mammoth bull market usually requires a catalyst. Inflation has the pole position to be that trigger, in my view, as 2021 dissolves into history. The bright folks at against-the-herd money manager Crescat Capital have pointed out that when inflation runs much higher than interest rates — which is exactly the situation in late 2021 — the stock market derates on a P/E basis. This is a polite way of saying “lookout below”. In fairness, they note that this risk arises when real rates have been negative “for a long period of time” which has not been the case… yet. However, they further opine that it’s the first-time negative yields have occurred with record-high valuations.

A key reason why the 2021 inflation outburst is particularly problematic at this point is that it is already placing considerable pressure on the Fed to shut down its Magical Money Machine. If that happens, especially if it happens quickly, it could have a powerfully deleterious impact on the frothy-to-the-max

U.S. stock market. As I write this chapter, there is a developing riot in bond markets around the world as other central banks renounce their fanatical devotion to QE and MMT policies. Many of the yield spikes are truly breathtaking, particularly on the shorter end of the yield curve. Should this bond carnage spread to America, it might be the ultimate pinprick for what I believe has been the most outrageous example of mass speculation in the history of this once great nation.[ii]

[i] A fresh example of this recurring phenomenon happened in 2021 related to the once unstoppable Cathy Wood and her ARKK funds. Despite a punishing 60% decline from its February 2021 apex, her flagship ARKK Innovation fund remains up 300% since inception. Despite this, the aggregate return to investors, based on the timing of their inflows and outflows, is now negative, due to investors flooding it with money after it did its Blue Origin imitation.

[ii] After writing these words in late 2021, this is precisely what happened, even in the U.S.