Green Energy: A Bubble In Unrealistic Expectations

Chapter 9 (Complete)

Green Energy: A Bubble In Unrealistic Expectations

Europe’s shocking energy crisis

As I wrote previously, it amazes me how little of the debate in 2021 centered on the inflationary implications of the Great Green Energy Transition (GGET). Perhaps that’s because there is a built-in assumption that using more renewables should lower energy costs since the sun and the wind provide “free” power.

However, we will soon see that’s not the case; in fact, it’s my contention that it’s the opposite, and I’ve got some powerful company. BlackRock CEO Larry Fink, a very pro-ESG[i] firm, is one of the few members of Wall Street’s elite who admitted this in the summer of 2021. The story, however, received minimal press coverage and was quickly forgotten (though, obviously, not by me!).

This chapter will outline myriad reasons why I think Mr. Fink was telling it like it is… despite the political heat that could bring down upon him. [ii] First, though, I will avoid any discussion of whether humanity is the leading cause of global warming. For purposes of this analysis, let’s make the high-odds assumption that for now the green energy transition will continue to occur. (For those who would like a well-researched and clearly articulated overview of the climate debate, I highly recommend Unsettled by a former top energy expert and scientist from the Obama administration, Dr. Steve Koonin.)

The reason for the italicized “for now” is that I think it’s extremely probable that voters in many Western countries are going to become highly retaliatory toward energy policies that are already creating extreme hardship. Even though it’s only early autumn as I write these words, energy prices are experiencing unprecedented increases in Europe. Because it’s “over there”, most Americans were only vaguely aware of the severity of the situation. But the facts were shocking…

It was a perfect storm on the Continent as the fall of 2021 turned into the winter of 2022. Or perhaps it was the perfect non-storm as a major culprit in Europe’s current energy crisis has been a general lack of wind, becalming its many windmills. It’s also been unusually cloudy, which is saying something, especially for Northern Europe, inhibiting solar power output. Further, temperatures have been somewhat colder than normal, though not nearly to the degree — or very low degrees – which China is facing. This has left natural gas storage levels critically low. (Fortunately for the Continent, thus far the actual winter has been relatively mild.)

Consequently, “nat gas” prices went truly postal at the end of last year reaching roughly $170 per MegaWattHour (MWh) in late December, the highest ever. Now get ready for this one: that’s eight times what it was a year earlier. This has driven electricity prices to the equivalent of $250 per barrel in oil terms! Obviously, the term crisis isn’t hyperbole “over there”. In fact, I’d suggest it has truly become a mega-crisis. (As of early February 2022, they have been cut in half, thanks in part to a 40% surge in U.S. liquified natural gas shipments to Europe; yet, they are still four times their year ago level.)

Per best-selling author Bjorn Lomborg, 50 to 80 million Europeans were suffering from severe energy poverty even prior to the estimated $400 billion power cost surge in early 2022. Additionally, six million UK households may not be able to pay their energy bills this winter. In fact, because of this unprecedented energy cost explosion, the British populace is facing the most severe drop in living standards on record. Widespread social upheaval in Europe is a distinct risk considering that gas pump hikes of just 12 cents per gallon in France produced widespread unrest. Lending credence to this concern, the bloody riots in Kazakhstan in early January 2022, which caused Russia to send in paratroopers, were primarily attributed to surging energy costs.

Besides the escalating human suffering, which threatens to be truly catastrophic should the last month of winter 2022 turn out frigid, it’s also producing a boom in coal power. The Continent’s coal plants are running full out and lignite, the dirtiest of coal sources, is dominating the fuel mix. Therefore, Europe’s energy agony is also aggravating environmental degradation. As we should all know, using coal as an electricity feedstock is far more polluting than oil and, especially, natural gas.

Aggravating the growing humanitarian crisis, serious food shortages were developing after the exorbitant natural gas price surges forced most of England’s commercial production of CO2 to shut down. Per the London-based Financial Times during the fall of 2021: “Soaring gas prices have forced the closure of two large UK fertiliser plants, sparking warnings of a looming shortage of ammonium nitrate that could hit food supplies as record energy prices start to reverberate through the global economy.”

Please check out this chart from the super-savvy team at Doomberg that shows the literally vertical move in North American fertilizer prices. Moreover, the US and Canada have a tremendous cost advantage due to far cheaper natural gas which is a critical fertilizer in-put.

Source: Doomberg, Doomberg

In Spain, consumers were paying 40% more for electricity compared to the prior year. The Spanish government began resorting to price controls to soften the impact of these rapidly escalating costs. (But we all now know about how “well” those work, right?) Naturally, they hit the poorest hardest, which is typical of inflation, whether it is of the energy variety or of generalized price increases.

Normally, I’d say the cure for such extreme prices, was extreme prices, to slightly paraphrase the old axiom. But these days, I’m not so sure; in fact, I’m downright dubious. After all, the enormously influential International Energy Agency has recommended no new fossil fuel development after 2021 – “no new”, as in zero.

It’s because of pressure such as this that even though U.S. natural gas prices doubled in the fall of 2021 and were still up around 75% over 2020 as the year ended, the natural gas drilling count stayed flat. The last time prices were this high there were three times as many rigs working.

It was the same story with oil production. Most Americans don’t seem to realize it, but the U.S. has provided 90% of the planet’s crude output growth over the past decade. In other words, without America’s extraordinary shale oil production boom — which raised total oil output from around 5 million barrels per day in 2008 to 13 million barrels per day in 2019 — the world long ago would have had an acute shortage. (Excluding the Covid-wracked year of 2020, oil demand grows every year — strictly as a function of the developing world, by the way.)

Unquestionably, U.S. oil companies could substantially increase output, particularly in the Permian Basin, arguably (but not much) the most prolific oil-producing region in the world. However, with the Fed being pressured by Congress to punish banks that lend to any fossil fuel operator, and the overall extreme hostility toward domestic energy producers, why would they?

There is also tremendous pressure from Wall Street on these companies to be ESG compliant. This means reducing their carbon footprint. That’s tough to do while expanding the output of oil and gas. Further, investors, whether on Wall Street or on London’s equivalent, Lombard Street, or pretty much any Western financial center, are against U.S. energy companies increasing production. They would much rather see them buy back stock and pay out lush dividends. The companies are embracing that message. A leading CEO publicly mused to the effect that buying back his own shares at the prevailing extremely depressed valuations was a much better use of capital than drilling for oil.

One U.S. institutional broker reported that of his 400 clients, only one would consider investing in an energy company! Consequently, the fact that the industry is so detested means its shares are stunningly undervalued. How stunningly? Numerous U.S. oil and gas producers are trading at free cash flow yields of 10% to 15% and, in some cases, as high as 25%. (In early 2022, there seems to be a sentiment shift underway. The plethora of pundits who deemed energy “uninvestable” in 2021 are suddenly removing the “un”; it’s amazing what oil prices nearing $100, caused by crashing supplies, does to investor attitudes.)

In Europe, where the same pressures apply, one of its biggest energy companies is generating a 16% free cash flow yield. Moreover, that is based up an estimate of $60 per barrel oil, not the prevailing price of nearly $95, as I apply the final edits to this chapter.

Besides how vital the U.S. shale industry has been to global supplies, another much overlooked fact about shale production is its rapid decline nature. Most oil wells see their production taper off at just 4% or 5% per year. But with shale, that decline rate is 80% after just two years. (Because of the collapse in exploration activities in 2020 due to Covid, there are significantly fewer new wells coming online; thus, the production base is made up of older wells with slower decline rates, but it is still a far steeper cliff than with traditional wells.)

As a result, the globe’s most important swing producer has to come up with about 1.5 million barrels per day (bpd) of new output just to stay even (this was formerly about a 3 million bpd number due to both the factor mentioned above and the 1.5 million bpd drop in total U.S. oil production, from 13 million bpd to around 11.5 million bpd in 2021). Please realize that total U.S. oil production in 2008 was only around 5 million bpd. Thus, 1.5 million barrels per day is a lot of oil and requires considerable drilling and exploration activities. Again, this is merely to stay steady-state, much less grow.

The foregoing is why I wrote on multiple occasions in my newsletter during 2020, when the futures price for oil went below zero, that crude would have a spectacular price recovery later that year, and especially in 2021. Even as it rallied hard throughout most of last year, I continued to opine it had more upside. My repeated 2021 forecast in numerous of our EVAs was that with supply extremely challenged for the above reasons, and demand marching back, I felt we could see $100 crude in 2022, possibly even higher. With it knocking on the triple-digit door in February of this year, that prediction has nearly come to fruition.

Frankly, I believe many in the corridors of power would like to see oil trade that high as it will help catalyze the shift to renewable energy. But consumers are likely to have much different reaction — potentially, a violently different reaction.

You thought 2021’s gas prices were high?

Mike Rothman of Cornerstone Analytics has one of the best oil price forecasting records on Wall Street. Like me, he was vehemently bullish on oil after the Covid crash in the spring of 2020 (admittedly, his well-reasoned optimism was a key factor in my up-beat outlook). Here’s what he wrote in the late summer of 2021: “Our forecast for ’22 looks to see global oil production capacity exhausted late in the year and our balance suggests OPEC (and OPEC + participants) will face pressures to completely remove any quotas.” My expectation is that global supply will likely max out sometime in 2022, barring a powerful negative growth shock, such as a Covid variant even more vaccine-resistant than Delta or Omicron turning out much more virulent than it looks to be in early 2022. A significant supply deficit looks inevitable as global demand recovers and exceeds its pre-Covid level.

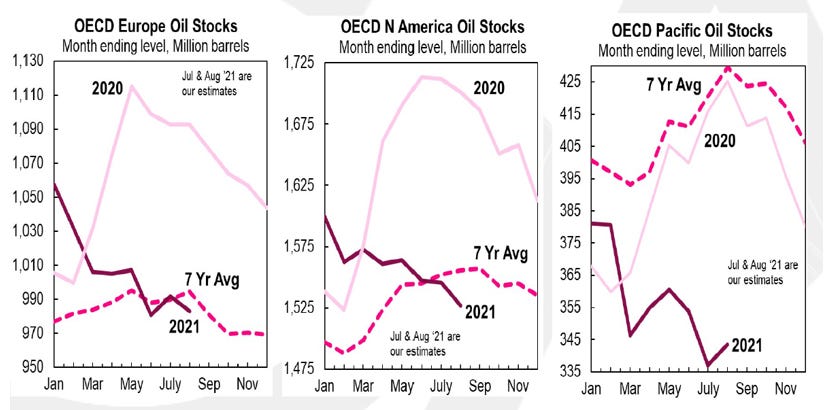

This is a view also shared by Goldman Sachs and Raymond James, among others; hence, my forecast of triple-digit prices next year. Raymond James pointed out that in June of 2021, the oil market was undersupplied by 2.5 mill bpd. Meanwhile, global petroleum demand was rapidly rising with expectations of nearly pre-Covid consumption by year-end. Mike Rothman ran this chart in a webcast on 9/10/2021 revealing how far below the seven-year average oil inventories had fallen. This supply deficit is very likely to become more acute in 2022. (For more on this topic, see the Appendix.)

Figure 1

In fact, despite oil prices having already moved over $70 in the early second half of 2021, total U.S. crude volumes were projected to actually decline. This is an unprecedented development. However, as the very pro-renewables Financial Times (the UK’s equivalent of The Wall Street Journal) explained in an August 11th, 2021, article: “Energy companies are in a bind. The old solution would be to invest more in raising gas production. But with most developed countries adopting plans to be ‘net zero’ on carbon emissions by 2050 or earlier, the appetite for throwing billions at long-term gas projects is diminished.”

The author, David Sheppard, went on to opine: “In the oil industry there are those who think a period of plus $100-a-barrel oil is on the horizon, as companies scale back investments in future supplies, while demand is expected to keep rising for most of this decade at a minimum.” (Emphasis mine) To which I say, precisely!

Thus, if he’s right about rising demand, as I believe he is, there is quite a collision looming between that reality and the high probability of long-term constrained supplies. One of the most relevant and fascinating Wall Street research reports I read as I was researching the topic of what I think can be referred to as “Greenflation” was from Morgan Stanley. Its title asked the provocative question: “With 64% of New Cars Now Electric, Why is Norway Still Using so Much Oil?”

While almost two-thirds of Norway’s new vehicle sales are EVs, a remarkable market share gain in just over a decade, in the U.S. the number is an ultra-modest 2%. Yet, per the Morgan Stanley piece, despite this extraordinary push into EVs, oil consumption in Norway has been stubbornly stable.

Coincidentally, that’s been the experience of the overall developed world over the past 10 years, as well: petroleum consumption largely flatlined. Where it hasn’t done an imitation of the EKG of a corpse is in the developing world, which includes China. As you can see from the following Cornerstone Analytics chart, China’s oil demand has vaulted by about 6 million barrels per day (bpd) since 2010 while its domestic crude output has, if anything, slightly contracted.

Figure 2

Another coincidence is that this 6 million bpd surge in China’s appetite for oil almost exactly matched the increase in U.S. oil production over the past 12 years. Once again, think where oil prices would be today without America’s shale oil boom.

China’s thirst for oil, as well as the rest of Asia’s, is unlikely to change over the next decade. By 2031, there are an estimated one billion Asian consumers moving up into the middle class. History is clear that higher incomes mean more energy consumption. Unquestionably, renewables will provide much of it, but oil and natural gas are just as unquestionably going to play a critical role. Underscoring that point, despite the exponential growth of renewables over the last 10 years, every fossil fuel category has seen increased usage globally, again, mostly a function of the developing world.

Thus, even if China gets up to Norway’s 64% EV market share of new car sales over the next decade, its oil usage is likely to continue to swell. As you may know, China has become the world’s largest market for EVs — by far. Despite that, the above chart vividly displays an immense increase in oil demand.

Here's a similar factoid that I ran in our December 4th, 2020, EVA, Totally Toxic “(There was) a study by the UN and the US government based on the Model for the Assessment of Greenhouse Gasses Induced Climate Change (MAGICC). It predicted that ‘the complete elimination of all fossil fuels in the US immediately would only restrict any increase in world temperature by less than one-tenth of one degree Celsius by 2050, and by less than one-fifth of one degree Celsius by 2100’. My apologies for asking a politically incorrect question, but if the world’s biggest carbon emitter on a per capita basis causes minimal improvement by going cold turkey on fossil fuels, are we making the right moves by allocating tens of trillions of dollars, that we don’t have, toward the currently in-vogue green energy transition?” Moreover, based on China’s recent no-show at the planet’s main climate change conference (COP 26) in Glasgow in 2021, it seems as though its fondness for fossil fuels isn’t likely to diminish.

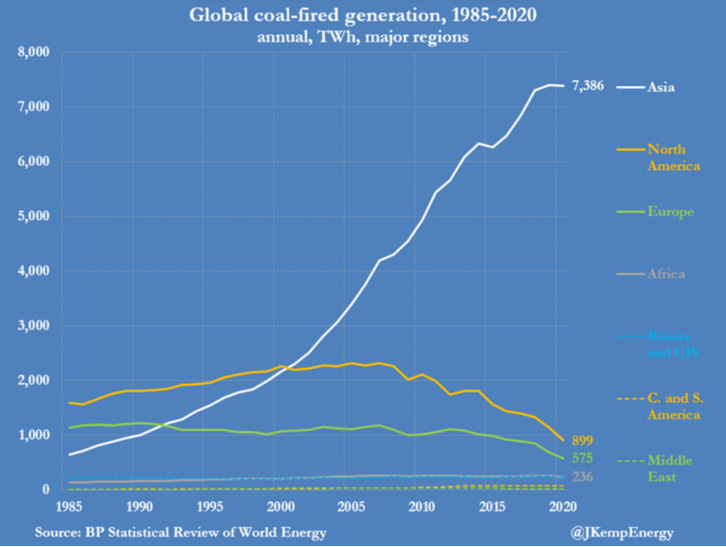

Another reason to expect China’s oil and gas needs to rise in the years ahead is its current heavy reliance on coal. In fact, 70% of China’s electricity is coal generated. Since EVs are charged off a grid that is primarily coal powered, carbon emissions actually rise as the number of such vehicles proliferate. As you can see in the following charts from Reuters’ crack energy expert John Kemp, Asia’s coal-fired generation has risen drastically in the last 20 year, even as it has receded in the rest of the world. (The flattening recently is almost certainly due to Covid, with a sharp upward resumption nearly a given.)

Figure 3

The worst part is that burning coal not only releases CO2 — which is not a pollutant and is essential for life — it also releases vast quantities of nitrous oxide (N20), especially on the scale of coal usage seen in Asia today. N20 is unquestionably a pollutant and a greenhouse gas hundreds of times more potent than CO2. (An interesting footnote is that over the last 550 million years, there have been very few times when the CO2 level has been as low, or lower, than it is today.)

Inconvenient realities

Some scientists believe one reason for the shrinkage of Arctic Sea ice in recent decades is the prevailing winds blowing black carbon soot over from Asia. This is a separate issue from N20, which is a colorless gas. As the black soot covers the snow and ice fields in Northern Canada, they become more absorbent of the sun’s radiation, thus causing more melting. (Source: “Weathering Climate Change” by Hugh Ross)

Due to exploding energy needs in China in 2021, coal prices have experienced an unprecedented surge. Despite this stunning rise, Chinese authorities have instructed its power providers to obtain coal and other baseload energy sources, such as liquified natural gas (LNG), regardless of cost. Notwithstanding how pricey coal has become, its usage in China was up 15% in the first half of 2021 versus first half 2019 which was, obviously, pre-Covid. Figure 4

Despite the polluting impact of heavy coal utilization, China is unlikely to turn away from it due to its high energy density (unlike renewables), its low cost and its abundance within its own borders. As we saw in Figure 2 above, it must heavily rely on oil imports to satisfy its 15 million bpd needs (about 15% of total global demand).

In yet another irony, China has a preference for U.S. oil because of its light and easy-to-refine nature, despite the current Cold War between the two superpowers. China’s refineries tend to be low-grade and unable to efficiently process heavier grades of crude, unlike the U.S. refining complex, which is highly sophisticated and prefers heavy oil such as from Canada and Venezuela — back when the latter actually produced oil.

Thus, China likes EVs because they can be de facto coal powered, lessening its dangerous reliance on imported oil. It also has an affinity for them due to the fact it controls 80% of the lithium-ion battery supply and 60% of the planet’s rare earth minerals both of which are essential to EV manufacturing.

However, even for China, mining and processing enough lithium, cobalt, nickel, copper, aluminum, and the other essential minerals/metals to meet the ambitious goals of largely electrifying new vehicle volumes, is going to be extremely daunting. Then there is its goal of mass wind farm construction and enormously expanded solar panel manufacturing

As energy expert par excellence Daniel Yergin writes: “With the move to electric cars, demand for critical minerals will skyrocket (lithium up 4300%, cobalt and nickel up 2500%), with an electric vehicle using 6 times more minerals than a conventional car and a wind turbine using 9 times more minerals than a gas-fueled power plant. The resources needed for the ‘mineral-intensive energy system’ of the future are also highly concentrated in relatively few countries. Whereas the top 3 oil producers in the world are responsible for about 30 percent of total liquids production, the top 3 lithium producers control more than 80% of supply. China controls 60% of rare earths output needed for wind towers; the Democratic Republic of the Congo, 70% of the cobalt required for EV batteries.”

As many have noted, the environmental impact of needing to immensely ramp up the mining of these materials is undoubtedly going to be severe. Michael Shellenberger, a lifelong environmental activist, has been particularly vociferous in his condemnation of the dominant view that only renewables can solve the planet’s energy needs. He’s especially critical of how his fellow environmentalists resorted to repetitive deceptions, in his view, to undercut nuclear power in past decades. By leaving nuclear energy out of the solution set, he foresees a disastrous impact on the planet due to the massive scale (he’d opine, impossibly massive) of resource mining that needs to occur. (His book, Apocalypse Never, is also one I highly recommend; like Dr. Koonin, he hails from the left end of the political spectrum.)

Putting aside the environmental ravages of developing rare earth minerals, when you have such high and rapidly rising demand colliding with limited supply, prices are likely to go vertical. This will be another inflationary “forcing”, a favorite term of climate scientists, caused by the Great Green Energy Transition. Per Pickering Energy Partners: “The capital intensity of the Energy Transition is unlike anything that we have seen. Relative to 2020 investment rates, spending needs to increase about 10x and hold steady for the next three decades.

Moreover, EVs are very semiconductor intensive. With semis already in serious short supply, as we saw in Chapter 8, this is going to make a gnarly situation even gnarlier. It’s logical to expect there will be recurring shortages of chips over the next decade for this reason alone, not to mention the acute need for semis as the “internet of things” moves into primetime.

In several of the newsletters I’ve written in recent years, I’ve pointed out the present vulnerability of the U.S. electric grid. Yet, it will be essential not just to keep it from breaking down under its current load; it must be drastically enhanced, a herculean task. For one thing, it is excruciatingly hard to install new power lines. As J.P. Morgan’s Michael Cembalest has written: “Grid expansion can be a hornet’s nest of cost, complexity and NIMBYism, particularly in the US.” The grid’s frailty, even under today’s demands (i.e., much less than what lies ahead as tens of millions of new EVs plug into it) is particularly obvious in California. However, severe winter weather in 2021 exposed the grid weakness even in energy-rich Texas, which also has a generally welcoming attitude toward infrastructure upgrading and expansion.

Yet it’s the Golden State, home to 40 million Americans, and the fifth largest economy in the world if it was its own country – which it occasionally acts like it wants to be – that is leading the charge to EVs and seeking to eliminate internal combustion engines (ICEs) as quickly as possible. Even now, blackouts and brownouts are becoming increasingly common. Seemingly convinced it must be a role model for the planet, it’s trying desperately to reduce its emissions, which are less than 1% of the global total, at the expense of rendering its energy system more similar to a developing country. In addition to very high electricity costs per kilowatt hour (its mild climate helps offset those), it also has gasoline prices that are 77% above the national average.

Voters in the reliably blue state of California may become extremely restive, particularly as they look to Asia and see new coal plants being built at a fever pitch. The data will become clear that as America keeps decarbonizing – as it has done for 30 years, mostly due to the displacement of coal by gas in the U.S. electrical system — Asia will continue to go the other way. (By the way, electricity represents the largest share of CO2 emissions, at roughly 25%.)

California has always seemed to lead social trends in this country, as it is doing again with the GGET. The objective is noble, though extremely ambitious, especially the timeline. As it brings its power paradigm to the rest of America, especially its vulnerable grid, it will be interesting to see how voters react in other states as the cost of power leaps higher and its dependability heads lower. It’s reasonable to speculate we may be on the verge of witnessing the Californication of the U.S. energy system.

In case you think I’m being hyperbolic, the IEA has estimated it will cost the planet $5 trillion per year to achieve net zero emissions. This is compared to global GDP of roughly $85 trillion. Frankly, based on the history of gigantic cost overruns on most government-sponsored major infrastructure projects, I’m inclined to take the over — way over — on the $5 trillion estimate.

Moreover, energy consulting firm T2 and Associates, has guesstimated electrifying the U.S. to the extent necessary to eliminate the direct consumption of fuel (i.e., gasoline, natural gas, coal, etc.) would cost between $18 trillion and $29 trillion. Again, taking into account how these ambitious efforts have played out in the past, I suspect $29 trillion is light. Regardless, even $18 trillion is a stunner, despite the reality we have all gotten numb to numbers with trillions attached to them. For perspective, the total towering level of U.S. federal debt is around $30 trillion (unfunded entitlements may sum to as much as $150 trillion per pundits such as Jeff Gundlach).[iii]

Regardless, as noted at the start of this chapter, the probabilities of the Great Green Energy Transition happening are extremely high. Similarly, I believe the likelihood of the Great Greenflation is right up there with them. While it would be unfair to blame the Fed for this particular inflation forcing, per earlier comments it is now being instructed to become involved in fighting climate change. This includes mounting pressure on it to penalize banks that invest in fossil fuel projects. If anyone at the Fed believes this poses extreme economic risks, their silence is deafening.

As Gavekal’s Didier Darcet wrote in mid-August of 2021: “Nowadays, and this is a great first in history, governments will commit considerable financial resources they do not have in the extraction of very weakly concentrated energy.” (my note: i.e., less efficient) “The bet is very risky, and if it fails, what next? The modern economy would not withstand expensive energy, or worse, lack of energy.”

While I agree this an historical first, it’s definitely not great (with apologies for all the “greats”). This is particularly not great for keeping inflation subdued, as well as for attempting to break out of the growth quagmire the Western world has been in for the last two decades.

In my view, as I’ve written in my newsletters, we are entering the third energy crisis of the last 50 years. If I’m right, it will be characterized by recurring bouts of triple-digit oil prices in the years to come. Along with Richard Nixon taking the U.S. off the Gold Standard in 1971, as discussed in Chapter 5, the high inflation of the 1970s was caused by the first two energy crises (the 1973 Arab Oil Embargo and the 1979 Iranian Revolution). If I’m correct about this being the third, it’s coming at a most inopportune time with the U.S. in hyper-MMT mode (per Chapter 7).

The sharp and politically uncomfortable rise in U.S. gas pump prices in the summer of 2021 caused the Biden administration to plead with OPEC to lift its volume quotas. The ironic implication of that exhortation was glaringly obvious, as was the inefficiency and pollution consequences of shipping oil thousands of miles across the Atlantic. (Oil tankers are a significant source of emissions.) This was as opposed to utilizing domestic oil output, as well as crude from Canada (which is actually generally better suited to the U.S. refining complex). Beyond the pollution aspect, imported oil obviously worsens America’s massive trade deficit – which would be far more massive without the 11.5 million barrels per day of domestic oil volumes – and would cost our nation high-paying jobs.

Surely, there are better ways of coping with the harmful aspects of fossil fuel-based energy than the scorched earth policies of some activists. (Literally, in the case of one Swedish professor who has written a book on blowing up oil and gas pipelines; he was inexcusably given a platform by the venerable The New Yorker.) Less violent, but seriously harmful, anti-energy policies include blocking new pipeline builds, shutting existing ones, and efforts to seriously restrict U.S. energy production. In America’s case the result will be forcing us to unnecessarily and increasingly rely on overseas imports. (For example, per The Wall Street Journal, drilling permits on federal land have crashed to 171 in August from 671 in April of 2021 despite rapidly rising oil prices.)

More rational solutions include fast-tracking small, modular nuclear reactors, encouraging the further switch from burning coal to natural gas (a trend that is, unfortunately, going the other way now, as noted above), utilizing and enhancing carbon and methane capture at the point of emission, including improving tailpipe effluent reduction technology; enhancing pipeline integrity to inhibit methane leaks; among many other mitigation techniques. The essential consideration is to recognize the reality that the global economy will be reliant on fossil fuels for many years, if not decades, to come.

If the climate change movement fails to acknowledge the indispensable nature of fossil fuels, it will almost certainly trigger a popular backlash, undermining the positive change it is trying to achieve. This is similar to what it did via its relentless assault on nuclear power in the 1970s, which produced a frenzy of coal plant construction in the 1980s and 1990s. On this point, it’s interesting to see how quickly Europe is reembracing coal power to alleviate the energy poverty and rationing occurring over there in late 2021 and early 2022. It has also now categorized natural gas and nuclear power as green energy sources, infuriating the extreme faction of the environmental movement. However, in my view, that was a big step toward political pragmatism. When the choice is between supporting climate change initiatives on the one hand and being able to heat your home and provide for your family on the other, is there really any doubt about which option the majority of voters will select?

Moreover, one of my other big fears is that the West is engaging in unilateral energy disarmament. Russia and China are likely the major beneficiaries of this dangerous scenario. (Please see the Appendix for an elaboration on this point.)

In 2011, the Nord Stream system of pipelines running under the Baltic Sea from northern Russia began delivering gas west from northern Russia to the German coastal city of Greifswald. For years, the Russians sought to build a parallel system with the inventive name of Nord Stream 2. The U.S. government fought its approval on security grounds, but the Biden administration has dropped its opposition. It appears Nord Stream 2 will happen, leaving Europe even more exposed to Russian coercion.

A closing thought for this chapter: Is it possible the Russian government and the Chinese Communist Party have been secretly and aggressively supporting the anti-fossil fuel movements in America? In my mind, it seems not only possible but probable. After all, wouldn’t it be in both of their geopolitical interests to see the U.S. once again caught in a cycle of debilitating inflation, ensnared by the twin traps of MMT and the third energy crisis?

[i] I.E., per the Glossary, supporting Environmental, Social, Governance acceptable standards.

[ii] For another perspective on energy inflation and Mr. Fink, please see the Appendix.

[iii] Further driving home the probability of a multi-trillion-dollar annual price tag, at the 2021 COP 26 in Glasgow, India demanded $1 trillion from the OECD (i.e., developed countries) to fund its decarbonization efforts. Thus, it may be a situation where greenflation intersects with greenmail.