The Biggest Bubble Inside The Biggest Bubble Ever

Chapter 11, Complete

Picking the low-hanging fruit

Are U.S. stocks more overvalued than at any time other than 1929 or 1999? Or are they even more expensive? Or are they reasonably priced, as so many media commentators and Wall Street strategists contend?

The answer somewhat reminds me of the old story of various people applying to be hired as an accountant at a certain firm. The owner asks each applicant what two plus two equals. The first dozen or so give the obvious reply and the boss politely but quickly dismisses them. Finally, one cagey interviewee (who clearly shows the mindset to be the CFO of a publicly traded corporation) answers: “Whatever you want it to be.” Of course, this person was hired.

Depending on which methodology you use, you can come up with whatever answer you want. (Please see the Appendix for a listing of some of the more popular valuation techniques.) Debating this with true believers, using whatever is their preferred metric, is nearly akin to arguing the articles of faith with an ardent Jew, Christian, Muslim or Buddhist. (Wait a second, do Buddhists argue?)

In this chapter, I’m going to tread on much safer ground. Instead of tackling the great stock-valuation debate, my focus is on a market that, frankly, most investors ignore – the one that is made up of those sleepy instruments known as bonds. (In Chapter 14, I will wade into those hazardous stock valuation waters.)

However, bonds being off the radar of the majority of market participants doesn’t mean they aren’t important. The fact alone that central banks have pumped nearly all of the $11 trillion they’ve digitally fabricated, since Covid struck, into fixed-income securities is proof-positive of their importance. Or, looking at it a bit differently, while not many people care about bonds per se, almost everyone cares a lot about interest rates, especially when they are paying or receiving them, as nearly all of us do at some point.

Fixed Income 101 tells us bond prices and interest rates move inversely, as discussed in Chapter 5. As a refresher, when a bond’s market value increases, its yield decreases. When yields fall in a big way, the returns can be surprisingly equity-like.

For example, the bond shown below issued by mid-stream-energy titan Enterprise Products produced a 20% per year return if purchased close to its early 2016 trough and held for the next 30 months. It happened again during the Covid-induced panic in the spring of 2020, as you can also see.

Figure 1

After crashing 37.5% almost overnight, this thrashing raised its current yield to 6.2% (roughly four full percentage points, or 400 basis points, over long-term treasuries). It then screamed back up 55% by the summer of 2021, providing those who summoned the courage to buy it during the worst of the virus crisis with a total return (i.e., including the aforementioned 6.2% yield) of nearly 65%! Rather punchy, don’t you think, for a low-risk security?

(Please see the Appendix for a listing of some of the more popular valuation techniques.)

Similarly, I doubt most gung-ho stock investors (isn’t that almost everyone these days?) are aware of the below total return comparison between the 30-year zero-coupon treasury bond and the S&P since the dawn of this century/millennium. Or let’s get even more extreme and look at the return in U.S. dollars on a long-term German government bond (known as a “bund”) and the supposedly nearly-impossible-to-equal, much less beat, S&P 500.

Figure 2

Figure 3

Let the protests begin!

The sound of all the equity cultists vociferously objecting is already ringing in my ears. Of course, they say, what do you expect? Central banks have ridiculously and massively distorted almost all major bond markets. And you know what? They’re absolutely right – $11 trillion of binge printing by the planet’s monetary mandarins couldn’t help but have an impact.

In fact, even though interest rates have been rising around the world as 2021 faded into the history books, there were still nearly $14 trillion of bonds that “produce” negative yields (production like that is reminiscent of the old Soviet Union). This is despite the fact that rates had been erratically rising during the year. Incredibly, more than a dozen years past the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), the world remains heavily populated with bonds which investors pay the borrower for the “privilege” of investing.[i] There are even banks in Portugal and Denmark that pay homeowners interest on their mortgages. Almost certainly, future generations will look back in bewilderment about this strange and nonsensical phenomenon, not to mention countless others that are equally bizarre.

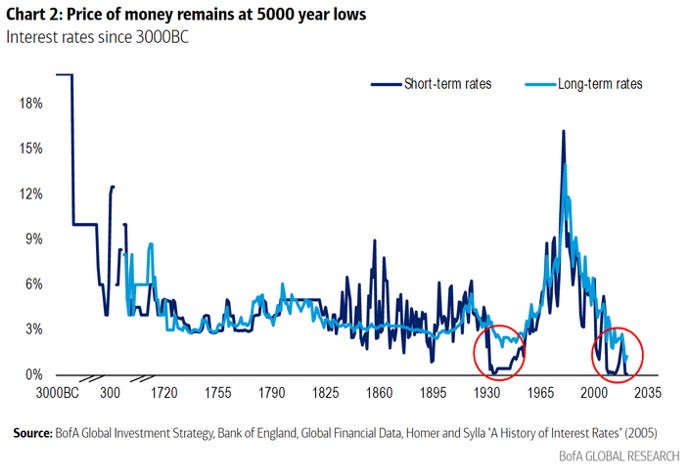

Even in the U.S., which has among the highest yields of any developed (G7) country, interest rates were at levels that in pre-crisis days would have been considered deep recession, almost depression, level. In fact, long-term treasury bond yields are lower in early 2022 than they were in the 1930s. Moreover, this is despite the current roughly 6% inflation rate. As a result, it’s hard to argue that bonds haven’t been, and basically still are, caught up in the biggest bubble in recorded human history. The only time they’ve been lower was briefly in the months following Covid going viral (literally). (Please see the Appendix for an eye-opening meeting Charles Gave had with a client of GaveKal’s on this topic back in 2019.)

The extraordinary power of interest rates

Unquestionably, Covid played a big part in forcing interest rates down somewhat further, but the reality is bond yields were extraordinarily depressed even before the pandemic. In most developed countries, near-zero and negative interest rates have been as persistent as sluggish growth and enormous government deficits. Could there be a connection?

It’s simply a fact, not an opinion, that the recovery by the U.S. economy from the Great Recession of 2009 was the weakest of the post-WWII era. You can go all the way back to the early 1920s and observe that reality.

Figure 4

Most overseas advanced economies fared even worse from 2009 through 2019, despite the fact that deep recessions, which the financial crisis unquestionably produced, typically lead to powerful recoveries. You can observe that in the chart above looking at the Great Depression-racked 1930s. Pre-pandemic there was only one G7 country that did not resort to the quantitative easing (QE) “remedy” (post-pandemic, it did). It was also the only one that economically outperformed the U.S., our good neighbor to the north. Accordingly, it’s not unreasonable to wonder if money fabrication on a massive scale actually works against real growth (as opposed to the growth illusion caused by inflation).

Figure 5

A prime factor in why zero and, especially, negative interest rate policies have failed to bring home the economic bacon was their effect on the banking system. As the top-notch bond guru Jim Bianco has cogently noted: “…the fractional reserve banking system is leveraged to interest rates. This works when rates are positive. Loans are made and securities bought because they will generate income for the bank. In a negative rate environment, the bank must pay to hold loans and securities. In other words, banks would be punished for providing credit, which is the lifeblood of an economy.” His take seems pretty rational about fractional, as in banking, don’t you think? Of course, that assumes stoking healthy economic growth was the main objective.

Or was this extraordinary, unprecedented, monetary manipulation intended to raise inflation to the 2% level with which central bankers today are so obsessed? Putting aside the question as to why it is desirable to erode a currency’s purchasing power by 45% over 30 years — which is what 2% inflation produces in that length of time — is it worth expending trillions to move the CPI up by, say, ½%?

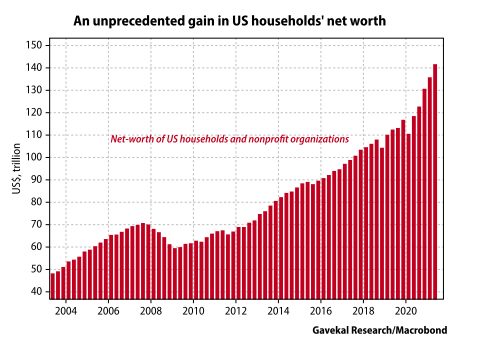

Alternatively, was it the goal of central banks to drive asset prices to extreme (some, like me, would say insane) levels in order to create a wealth effect, thereby turbocharging economic growth? If so – and former Fed head Ben Bernanke plainly stated years ago that was the goal – have they succeeded? Per the above image about the reality of how deficient this expansion has been, it’s hard to argue that the Fed succeeded on economic grounds.

But when it comes to asset prices, the tsunami of trillions, and the related collapse in interest rates, has swamped all those, like me, who dared to question the wisdom of incessant QEs which have now morphed into MMT, particularly in the U.S. When the original version of this chapter ran in our September 2018 EVA, we published an article by Reuters columnist Edward Chancellor titled The Mother of All Speculative Bubbles, obviously, a most relevant piece for the main thesis of this book.

In the opening section, he gets right to the heart of the matter — or mania – by quoting the father of economics, Adam Smith, on the impact of interest rates on property prices a few years ago — like back in the 1700s! In 1776, English man of letters Horace Walpole observed a “rage of building everywhere”. At the time, the yield on English government bonds, known as “Consols”, had fallen sharply and mortgages could be had at 3.5 percent. These days, mortgages rates at that level would be considered usurious in Europe!

In The Wealth of Nations, published the year of America’s war of independence from England began, Adam Smith observed that the recent decline in interest rates had pushed up land prices: “When interest was at ten percent, land was commonly sold for ten or twelve years’ purchase. As the interest rate sunk to six, five and four percent, the purchase of land rose to twenty, five-and-twenty, and thirty years’ purchase.” [I.E., the yield on land ownership fell from 10 percent to 3.3 percent; he’s essentially describing a falling “cap rate” to use current real estate vernacular]. Smith explains why: “the ordinary price of land ... depends everywhere upon the ordinary market rate of interest.” That’s because the interest rate discounts, and places a capital value, on future income. Undoubtedly, were Mr. Smith still on this side of the grass, he would be dumbfounded and horrified by the specter of negative interest rates. Equally surely, he would assert they lead to myriad distortions and excesses.[ii]

Among the latter, of course, would be real estate valuations soaring to outrageous heights, which is exactly what has happened. This creates assorted societal ills including, as mentioned in earlier chapters, unaffordable housing and exaggerated wealth disparities between those who own and those who rent.

All the great past speculative bubbles – from the tulip mania of the 1630s up to the global credit bonanza of the first decade of this millennium – have occurred at times when interest rates were abnormally low. The basic point is that as interest rates plunge to ultra-depressed levels, buyers are willing to pay higher and higher prices for income-producing real estate. (When Adam Smith used the term “purchase” he was referring to annual cash flow.) Admittedly, that’s not a brilliant insight for real estate-savvy individuals, but I suspect most of them have been amazed by how long de minimis interest rates have persisted during this cycle.

Consequently, this has led to the longest bull market in property prices on record, one that has become a bona fide super-cycle, notwithstanding a brief hiccup during the worst of the Covid lockdowns. Stories of astounding transaction prices in late 2021 are as common as bad policy decisions in Washington, D.C.

If one accepts the reality (and not to is denying same) that recent years have seen the lowest interest rates in 5000 years, as we saw in Chapter 5, then how could we not be at least going through a massive bubble, if not, as I’ve contended, the Biggest Bubble In Recorded Human History or BBIRHH.

Figure 6

Will they EVER learn?

While acknowledging Sweden isn’t the most systemically critical country on the planet, it is nonetheless an interesting (sorry) case study in what insanely low interest rates can cause. First, for those of you who don’t waste your life studying these things like I do, Sweden had a monstrous housing bubble in the early 1990s. And like ALL bubbles ultimately do, it popped — big time. The implosion was so cataclysmic that it wiped out the staid nation’s banking system. Additionally, as is nearly always the case, it triggered a severe recession. (For more on this crisis and its parallels with our own housing bubble of 15 years ago, please see the Appendix.)

One might think that such an experience would cause Swedish policymakers to do everything in their power to prevent a repeat performance. But, then again, one would also think the brainiacs at America’s Federal Reserve would be extremely bubble-averse after what happened from 2000 to 2002 and then again in 2008. In both cases, one would have been wrong — like dead wrong.[iii]

In Sweden’s case, it was the world’s fastest growing developed country in 2015, with real growth cresting at 5%. Yet, in its central bank’s infinite wisdom, its official interest rate was MINUS 0.5%. And, as predictably as the Fed continuing to make erroneous economic forecasts, including totally missing 2021’s inflation spike, Swedish home prices did a moonshot.

As you can see below, Sweden made the top ten of riskiest housing markets with an estimated 165% overvaluation. This list also gives you the sense of the global nature of the latest housing bubble. The U.S. didn’t even make the top ten despite the outrageous pricing in cities like Seattle, San Francisco, LA, New York and Washington, D.C. As we know, since this table was published in 2017 prices have levitated higher yet. Figure 7

As with the stock market, Covid has had a perverse impact on home valuations, sending them much higher despite all of the economic distress the pandemic produced. There’s scant question that central banks drenching the planet with trillions of their quasi-counterfeit money was behind this odd development.

Prior to Covid, Swedish home prices were beginning to crack. One of Sweden’s largest developers was slashing prices 15% to 20% in its main Stockholm projects. Home prices in one of Stockholm’s wealthiest suburbs fell 17% through July 2018.

The softness was global. In Australia, prices fell for 11 straight months in 2018. Aussie banks were beginning to buckle and new revelations about imprudent, and even illegal, lending practices by major financial institutions Down Under were coming to light on a regular basis. Canada’s bubbly property market was also coming off the boil pre-Covid.

America was feeling the pain, too. In the Big Apple, the formerly ripping Manhattan housing market, saw the median price per square foot tumble a shocking 18% in late 2018. Even white-hot Seattle real estate prices slid, falling 6% in one month alone in 2018. Apartment rents melted 10% in the Emerald City during 2018 despite a robust economy due to Amazon, Microsoft, et al, and their expanding Seattle-area footprint. California cities were also seeing price declines, a very unusual development.

But, as noted, Covid changed the calculus, demonstrating that even a worldwide pandemic is no match for the power of the collective central banks’ Magical Money Machines. Even in cities like Seattle, where thousands of residents were, and still are, decamping in droves, prices moved higher. But home inflation was far more pronounced in the outlying areas where residents have been fleeing to safer venues. In West Bellevue, just across the lake from Seattle, it’s not uncommon for lots to sell for $4 million, or even more, (yes, just the dirt and non-waterfront, by the way) in late 2021.

As a result, what was an immense bubble in asset prices prior to the pandemic became even more so. Housing prices in most major cities around the world far exceeded the levels of 2007, considered at the time the greatest real estate bubble ever.

The bond market, severely distorted by central bank interventions, kept interest rates suppressed even as inflation soared throughout 2021. This produced deeply negative real yields, shunting even more money into stocks and real estate. Accordingly, the bond market was unquestionably a huge factor in the exceedingly hazardous asset overvaluation shown below.

Figure 8

One of the many harmful aspects of negative yields, including positive nominal yields that are in the red after taking inflation into account, is what they do to productivity. With virtually the entire developed world facing the reality of deeply negative real rates, this is an extraordinarily important point to ponder. Per the below chart, you can see the impact on productivity, going back nearly 70 years, of these episodes when inflation exceeds the return on savings vehicles like T-bills.

Figure 9

The following chart from bond behemoth Double Line — where the Bond King, Jeffrey Gundlach, is the undisputed ruler — illustrates just how exceptional the last decade has been in that regard. Even the inflation-plagued 1970s weren’t as extreme in this regard.

Figure 10

(show Double Line chart that I emailed to Christina and Mark on 2/12/22; might need to go to their website or get a better one from Gherman if it’s not locatable).

And while excessively low rates are great for real estate, there is a dark side to that with regards to productivity. As increasing amounts of capital flows into existing homes, apartments and commercial buildings, there is less money invested in assets that actually enhance productivity. As The Wall Street Journal wrote on this topic in a November 28, 2020, article: “For every 10% increase in real estate prices, an industry would record a 0.6% decline in total-factor-productivity due the effect of skewed capital allocation.”

Moreover, once the property bubble pops, there is enormous wealth destruction such as we saw from 2007 to 2010 when the housing market crashed. This creates a massive drag on a nation’s productive capabilities. In America’s case, it has led to multiple rounds of the Fed’s binge printing technique we have come to know as QEs 1, 2 and 3 (plus a fourth unofficial version). To say this entire approach has failed to deliver rewards commensurate with its immense costs is being exceedingly charitable to our grand and glorious central bank.

The corporate bond market: A case of Icarus syndrome?

A critical part of the bond market, and one that has played key roles in numerous financial crises and recoveries, is corporate debt. My hope that among the most lasting concepts readers glean from this book is the extreme criticality of credit spreads. Once again, these reflect the difference between what corporate borrowers pay in terms of interest on their debt and what the government pays on treasuries. When that gap, or spread, widens significantly, it almost always means corporate bond prices are under downward pressure.

Often during these episodes, the price declines can be severe, as seen with the debt shown above involving Enterprise Products (arguably, but not much, the strongest of the independent energy infrastructure operators). When conditions improve, the rallies can be extraordinary, as the Enterprise bond chart above clearly shows. Rapidly declining (aka, narrowing) credit spreads are like mixing Red Bull with a double espresso when it comes to hyper-stimulating a bull market in both stocks and bonds.

The ultimate proof of just how vital credit spreads are occurred, as described in Chapter 2, when the Fed announced it was buying corporate bonds during the worst of the virus crisis. As also noted earlier, it was this disclosure that ended the shortest bear market and recession of all time. While it wasn’t the only catalyst, in my view it was the most powerful one… by far.

During the pandemic’s sheer panic phase, in the first few weeks of March of 2020, credit spreads blew out, as they nearly always do during high-stress times. But, unlike 2008-2009, the Fed prevented it from being a drawn out, death-by-a-thousand cuts affair (which is what the Global Financial Crisis experience felt like — take it from someone who bled plenty back then!). As with stocks and the economy, the corporate bond market rally and the tightly linked spread contraction were breathtaking.

Figure 11

As a result of this screaming rally in corporate bonds, spreads are now extremely tight. Thus, not only are rates at historic lows relative to inflation, credit spreads are, as well. On the former, never has the yield on the 10-year T-note been 4 ½% below the CPI increase on social security.

Similarly, 2021 saw the economy’s nominal growth rate (again, real growth plus inflation, as explained in the Glossary) exceed the yield on the 10-year treasury by the widest margin on record.[iv] Most significantly, this had the effect of reducing the U.S. government’s debt-to-GDP down by 13 full percentage points in a year, from 135% to 122%. In my view, this is precisely what the powers-that-be wanted to bring about — and still do. It’s basically a stealth form of default with bondholders taking a severe hit in terms of lost purchasing power. (This punitive action toward U.S. government debt owners is likely in its early stages.)

Related to how compressed both rates and spreads were in 2021’s fourth quarter, this is the first time less-than-investment-grade corporate bonds (junk), the ultimate spread vehicles, traded with negative real yields. In other words, it’s another example of a bond market that increasingly offers copious amounts of risk and precious little in the way of reward.

Accordingly, in the next crisis — one that could be precipitated, say, by millions of investors having an epiphany that rising inflation is becoming a persistent problem — corporate bond investors could lose twice: First, due to a big jump in rates and, second, as a function of materially widening credit spreads.

While not all stock market convulsions have been caused by spiking credit spreads, I’ve never seen a serious spread-widening episode that hasn’t triggered an equity downdraft. Typically, the more severe the spread widening, the more painful the correction in stocks. Consequently, even if you don’t give two hoots about bonds, because you’re an equity gal or guy, you should be aware of this aspect.

Besides unusually tight spreads and the putting green level of interest rates, there were also unmistakable signs of complacency and frothiness in the more esoteric realms of the non-government bond market in the fourth quarter of 2021. The currently highly popular Collateralized Loan Obligation (CLO) market is almost a carbon copy (yes, I know I’m dating myself, perhaps carbon-dating myself) of the Collateralized Debt Obligation (CDO) space. It was these not-so-secure securities that nearly destroyed the planet’s financial system a dozen years ago.

Regardless, the ducks were loudly quacking again in late 2021 to be fed more yield products, with CLOs being hoovered up like spilled popcorn in a theater after a Spider-Man: No Way Home showing. This is notwithstanding that CLO yields were pathetically low and their credit risks disturbingly high.

Moreover, bond covenants meant to protect fixed-income investors had once again become exceedingly lax (favoring the borrower over the lender), as was the case leading up to the Global Financial Crisis. The term “bond” is supposed to mean exactly that: an explicit and enforceable contract between the issuer and the investor. Yet, as happens regularly when there is yield starvation — and, as I write these words, there is a mass yield famine afflicting fixed-income land — borrowers are in the driver’s seat. And, when that happens, they never fail to drive some brutally hard bargains, such as being allowed to skip interest payments without having to declare bankruptcy.

Returning to junk bonds, Michael Lewitt, the bubble-busting author of the Credit Strategist, wrote in his October 1st, 2021, issue: “Even though these instruments are called ‘bonds’, they offer few if any of the traditional protections traditionally associated with bonds. So in addition to offering negative real yields, they offer no covenants and limited liquidity.”

His last point is an important one, particularly with the wild popularity in recent years of junk bond ETFs. These allow investors to instantly buy and sell these securities which own around 1000 different underlying “high yield” bonds. The problem is that many of these trade by, as they say, appointment only.

In bull markets, that’s a no-worries situation, particularly when there is trillions in excess liquidity sloshing through the financial system. But when the inevitable ebb tide sets in, this creates the potential for severe price hits should investors decide to exit en masse, and in a hurry, as they so often do during turbulent periods. Because many of the underlying bonds are extremely illiquid, prices need to be deeply discounted in order to clear markets during a panic. You can see what it looked like for HYG and JNK, the two-leading junk bond ETFs, during March 2020.

Figure 12

Yet, despite negative after-inflation yields, junk bond buyers were ravenous as they absorbed record amounts of issuance, as 2021 drew to a close. Clearly, the prospects of losing money to inflation, the always substantial risk of default with most junk bonds, the liquidity problems, and the paucity of covenant protections, fazed investors not in the least.

It would be remiss on my part if I failed to point out that the unparalleled bond bubble played a starring role in the government debt saga. Pre-Covid, a decade of negligible, cum negative, interest rates enabled developed nations to pile up sovereign IOUs to levels not seen since WWII. Post-Covid, of course, the amount of governmental indebtedness reached almost incomprehensible proportions.

Figure 13

With throw-away interest rates, though, what’s the big deal? As you can see, interest costs as a percentage of the size of the Big Seven (G7) economies is a yawner.

Figure 14

It’s the same in the corporate world, as well, with accumulated debt amounting to $11 trillion or 49% of GDP, an all-time high. Yet, as you can see below, debt service for U.S. corporations is a breeze.

Figure 15

As extensively covered in Chapter 6 on MMT, this logic-defying controversial economic thesis has taken the enabling to an entirely new, and totally shocking, level. Politicians have discovered their dream machine and they are dreaming in fantastical ways that put Hollywood to shame. The multi-trillion question is if this will eventually turn into a nightmare, as have all prior full-blown MMTs (Japan is the lone exception and it did MMT-lite).

With an increasingly stubborn inflation trend dominating 2021 — and likely into 2022, as well — thereby undercutting the Fed’s transitory assertions, senior officials such as Jay Powell must have been sleeping very fitfully. As noted in the MMT chapter, inflation has consistently flipped the free-money fueled booms into busts. A central element of this denouement is a cost of capital, or interest rate, that is far too low (per the foregoing 250-year-old comments by Adam Smith). When this happens, asset bubbles are inevitable. Based on rates being the lowest ever and becoming rapidly more negative in real terms as inflation predictably took off in 2021, it’s no surprise we are witnessing the type of orgiastic speculation documented in Chapter 10.

Ludicrously low interest rates also lead to obscene misallocations of capital, like the stripper in The Big Short who was able to buy seven overpriced homes due to reckless lending practices. Capital misallocation is just a fancier name for a bubble. As we’ve seen in overwhelming detail, in late 2021 bubbles were as pervasive as liars in Washington, D.C. When future generations seek to do a forensic analysis of this evolving (devolving?) disaster, they will need to look no further than the Biggest Bubble Inside The Biggest Bubble In Recorded History. As you know by now, that would be the bond market.

[i] In the first six weeks of 2022, the biggest bond bubble in history has quickly become considerably less bubbly. Yields are rocketing around the world albeit from very low, often negative, levels. The stock of bonds with minus signs in front of their yields has fallen from $14 trillion to around $4 trillion in roughly two months. If nothing else, this validates the basic contention of this chapter about the exceptional vulnerability of global bond markets as I was initially writing it in the fourth quarter of 2021.

[ii] In 17th century England, manias were looked at just a bit askance. Per American author Chris Hedges, “Speculation in the 17th century was a crime. Speculators were hanged.” It’s a bit terrifying to think that if this was the law of the land in 21st century America, how many necks would be getting stretched.

[iii] Low rates, along with ultra-aggressive mortgage lending practices, were the two main contributing factors to the 2002 to 2007 housing bubble, which nearly obliterated the global financial system.

[iv] There may have been one other very brief episode in the early 1950s.