The maiden voyage of QE I

Returning to the great housing speculation of the first decade of this millennium, it’s my contention that its impact cannot be overemphasized. In my mind, it’s the main reason Western countries are now following monetary and fiscal policies formerly associated with Banana Republics. Moreover, there is a profound difference between the monetary (the Fed) and fiscal (the federal government) responses today, as a result of the virus crisis than was the case after housing crashed 12 years ago, as we shall soon see.

The collapse of Bubble 2.0 started out innocuously enough. Just months before what would soon be known as the Global Financial Crisis, it appeared that problems in housing might merely cause a mild recession. As noted in Chapter 2, Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke had assured the public that the melt-down in the mortgage market would stay “contained” within sub-prime loans. Other high government officials, like Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson, assured investors in Fannie and Freddie that those two government-sponsored entities (GSEs) were safe and sound. Within months, however, both Mr. Bernanke’s and Mr. Paulson’s soothing words would be proven utterly unsound.

It was almost like what had happened in another September, seven years earlier, on 9/11/01. Americans woke up one day and the world they had known was forever changed. Fear had replaced complacency and the speed with which it happened made it feel like some kind of terrible dream. In reality, the 2008 crash was another national nightmare and one that continues to haunt us to this day, despite the seeming invincibility of the S&P 500 (at least as of this writing). Even prior to Covid, Western central banks continued to follow financial crisis policies such as binge money printing (the digital version) and ultra-low to negative interest rates. Both have had powerful and, in many cases, seriously negative impacts on society at large. This contention will be defended in more detail in upcoming chapters.

Remarkably, after over a decade of evidence that these radical monetary experiments have failed to produce prior economic growth rates—and have severely aggravated wealth inequalities—central banks are fiercely adhering to Einstein’s definition of insanity: Doing the same thing, over and over, and expecting different results.

As discussed in Chapter 2, a prime factor as to why financial conditions deteriorated so rapidly in the fall of 2008 was the Fed initially greatly underestimated the magnitude of the crisis. Once it finally grasped the severity, it flew into action with a bold series of moves. It guaranteed money market funds which had suddenly become suspect in the minds of investors, to forestall a mass panic-stricken run on these widely held vehicles that were once considered riskless. It provided foreign central banks with enormous sums of desperately needed dollars. And, perhaps most significantly, the Fed prepared to launch its first round of Quantitative Easing (QE) whereby it willed into existence $1 trillion of reserves with nothing more than a few computer keystrokes.

This money-from-nothing was, of course, unprecedented. Never had the central bank of a wealthy country resorted to such an extreme monetary policy. It was intended to instill confidence and stabilize the system, but it had an unintended consequence. Because we have become so numb to QEs over the past decade plus, most of us forget the chorus of supposedly expert voices warning that such overt money printing[i] would lead to inflation, possibly of the hyper variety.

One reason I vividly remember this aspect is that for at least the first few years after QE 1.0 was launched, with three more iterations[ii] to follow, I repeatedly found myself in the position of debating the subject with clients and other investment professionals. Many of them contended that inflation was inevitable and, moreover, that it was exactly what the U.S. government wanted as a way of inflating away its debt. (The Federal deficit was exploding in those days due to the Great Recession and the numerous bailouts that also included GM and Chrysler.)

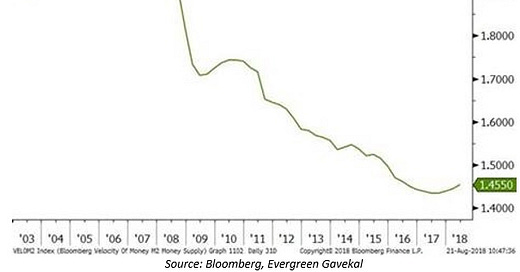

My counterargument was that offsetting the stimulus from the trillion-dollar QE was something of which very few people were aware: the velocity of money. While the Fed was synthesizing its first trillion, money velocity was cratering at a rate unseen since the Great Depression. (For a more thorough explanation of money velocity, please see the Chapter 4 Appendix.)

Figure 1

Paralysis by faulty analysis

Yet, because most people had never heard of the velocity of money and were only focused on the sheer quantity of quantitative easings, they fell victim to the idea that yield securities were to be avoided. This was most unfortunate, and likely cost investors hundreds of billions, if not trillions, in lost income as well as capital gains. This is due to the fact that, as described in Chapter 2, high cash-flow investments like non-government guaranteed mortgages, corporate bonds, and preferred stocks were selling at prices unseen since the early 1930s. During the worst of the crisis, junk bonds were trading at yields of around 23%! (In early 2022, by contrast, they are roughly 5%.)

Additionally, other income vehicles, like master limited partnerships (MLPs) and real estate investment trusts (REITs), were mercilessly pummeled, with their prices often slashed by 60% or more. In some cases, cash-flow yields on MLPs were over 30% and, in almost all instances, their distributions held.

As a consequence of this meltdown, Americans were not only terrified, they were furious. They were livid with policymakers for having been blind to the mortgage fiasco that many, including this author, had warned about for years. They were incensed that their money was being used to “bail out Wall Street”.

It was in late 2008, during the worst of the panic, that Congress reluctantly passed the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP). This legislation provided for the U.S. Treasury to infuse capital into large banks and insurance companies in return for a high interest rate and, critically, an equity stake. Of course, with all financial equities having been crushed, the government was receiving de facto equity at ultra-distressed valuations. (Once again, please refer to the Appendix for more on this underappreciated, but vital, subject.)

This prompted me to write at the time that the Treasury would eventually earn windfall profits. To say this view generated widespread derision is putting it very mildly. Many people thought I had lost it, an opinion I often hear. Yet, as we now know, or should, TARP became a monster moneymaker for taxpayers.

But, back then, the mantra was “Bail Out Nation” and the anger eventually led to the “Occupy Wall Street” movement (bet you forgot that one!). For those of a less militant nature, which would be most investors, the mindset was not so much vitriolic as paralytic. They were too traumatized to buy anything, despite the yields mentioned above, even once it was clear the financial system would not implode.

Meanwhile, junk bond yields were tumbling from 23% to the mid-teens and then into the single digits, as millions missed the chance to make billions. Many MLPs were in the process of tripling or more. As noted earlier, even high-grade corporate bonds were producing 30%-type returns off their late 2008 lows, and preferred stocks in major financial institutions were posting total returns of 50% during the first year of the recovery (with many more years of double-digit returns still to come).

Part of the reason investors were so reluctant to reengage with financial markets was due to the dire warnings that continued to be issued by many of the experts who were among the few to warn of the mortgage mayhem. Despite a stock market that had been more than cut in half, predictions of much greater declines — like Dow 5000 — were commonplace. And because these individuals had considerable credibility based on their housing crisis calls, it was hard to dismiss their views. One of these experts, whom I personally respect very much, repeatedly predicted a second Great Depression well into the recovery.

Due to the pervasive pessimism in the early years of the rise from the abyss, valuations stayed attractive. As late as the summer of 2011, over two years into the new bull market (as a side note, the previous bull lasted only five years, from 2002 to 2007), the median P/E ratio on the Dow was just 12. (Those were the days! Today, as mentioned earlier, that number is over 21.)

The income realm was a different story, however. Double-digit yields were long gone. MLPs and REITs had continued their furious rally that started in November 2008 and March 2009, respectively. By mid-2012, investment-grade bonds yields were a miserly 4% and the interest rate on junk bonds got down to 6% by summer’s end.

There were reasonable fears, though, that once the Fed quit creating money to buy government bonds, rates would rise dramatically. Yet, as with inflation, there was a surprise playing out. Treasury yields actually fell in anticipation of QEs I and II but then rose as the Fed began buying. Once the programs ended, rates declined again. (By the way, “OT” on the following chart refers to “Operation Twist”, another Fed tactic to bring down longer-term interest rates.)

Figure 2

Stability’s inherent instability

To the Fed’s great vexation, unemployment remained stubbornly high in the early years of the expansion, leading it to believe more monetary uppers were needed. In the fall of 2012, over three years into the economic up-cycle, it launched QE III. The third iteration would turn out to be the biggest of all, eventually totaling $1.6 trillion.

By the time it finally turned off its Magical Money Machine in October of 2014, the Fed’s balance sheet had exploded from around $700 billion pre-crisis to a Himalayan $4.5 trillion. There is little doubt much of this spilled over into asset prices, either directly or indirectly. (An indirect example is that by collapsing interest rates, the Fed encouraged publicly traded companies to leverage up to buy back their own shares, to the tune of about $5 trillion since 2010.)

In addition to fabricating almost $4 trillion, it also maintained interest rates at essentially zero until meekly hiking rates in December of 2015. In other words, the Fed kept the monetary pedal to the metal over five years into the recovery-cum-expansion. (Technically, a recovery is the post-recession phase that returns GDP back to its prior peak and the expansion is the GDP increase that occurs thereafter.) This was totally unprecedented in the annals of Fed monetary policy… but one that is eerily similar to what the Fed did again in 2020 and 2021.

Despite this unparalleled largess, and a near doubling of the national debt, not only was the jobless rate stubbornly high for many years, the expansion also turned out to be the weakest on record. (By the way, historically, the worse the recession, the stronger the recovery and expansion — and those prior vigorous rebounds were achieved without multi-trillion-dollar monetary stimulus.)

For example, in the 1980s recovery out of the deep Volcker-induced recession, real growth averaged 4.4% per year. Coming out of the S&L/real estate bust recession of 1990/1991, after-inflation growth came to 3.8% annually. But the expansion post the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) was a mere 1.8% per year in real terms. In other words, the economic return on the Fed’s three official QEs, plus the stealth one in 2019, was, with no exaggeration, pathetic.

As a result, it’s reasonable to question the efficacy of this epic experiment in flooding the system with liquidity and debt — at least as far as the economy is concerned. It was a completely different story for asset prices. Right before Covid struck, it was hard to find a major asset class that hadn’t been driven up to bubble-like prices, at least briefly. (One of the fascinating aspects of Bubble 3.0 has been its rolling nature, i.e., a particular asset class goes vertical, then crashes, as the cryptocurrencies did in 2018, while another one steps to center stage to become the latest moonshot – until it, too, plunges back to Earth.)

Another example, few would have foreseen, is that out of the smoking rubble of the real estate crash of 2008, prices would eventually exceed their 2007 peak. But that’s exactly what’s happened for both commercial and residential properties, even as early as 2018.

Figure 3

Yet more remarkable has been the post-Covid upside explosion in housing prices. As was the case a dozen years ago, the dark side of this has been an utter collapse in affordability.

Figure 4

(Home prices and affordability (or lack thereof) during the boom-&-bust years)

This is perhaps where the Fed’s policies have most gone awry (though there is a lot of competition for that characterization). Its massive monetary manufacturing has made the rich even richer and the stinking rich even stinkier[iii]

There’s scant doubt that the Fed’s asset inflation policies, so openly admitted to in the 2010 Washington Post Op-Ed by Ben Bernanke, have turbocharged financial and property markets. Since the rich own most of the assets, it’s axiomatic that such a ploy would disproportionately benefit the moneyed class. The synchronicity between the Fed’s monstrously expanded balance sheet, totally built up with its fabricated funds, and the stock market’s relentless ascent of the past twelve years is difficult to deny. Further, the vast expansion of wealth and its increasing concentration in the toppercentile, and the top decile within that (i.e., top 1/10th of 1%), is simply a statement of fact. Please see Figures 5 and 6 for the visual evidence of this[iv]

Figure 5

Figure 6

The stock market wealth concentration and extreme valuations are bad enough but housing being in the ionosphere presents more pressing societal concerns. The affordability, or lack thereof, highlighted above is why homeownership among millennials is unusually low. This is also a global phenomenon with some countries likes Canada, New Zealand, and the Netherlands beset by even more outrageous home prices. In certain Scandinavian countries, some homebuyers surrealistically receive a monthly check from their bank for their negative yielding mortgages but, regardless, younger people often still can’t afford to get on the housing carousel. Presumably, they can’t handle the down payment and/or the ongoing costs of ownership, especially property taxes which inflate with home prices. Regardless, prices are far above the levels they hit during what has long been viewed as the greatest housing bubble of all-time.

Figure 7

Per The Financial Times in a March 15th, 2021, article by Morgan Stanley Investment Management’s chief global strategist, Ruchir Sharma, 90% of 502 cities around the world are unaffordable, meaning prices are more than 3x median family income. In present-day Seoul, Korea, it takes 17 years of median yearly household income to purchase the average-priced home! (Source: Bloomberg Businessweek, 8/2/21)

Back in the U.S., it’s also hard to dismiss a linkage between the Fed’s multi-trillion balance sheet expansion and home purchase debt (i.e., mortgages). Is it sheer coincidence this looks so much like the chart of the Fed’s balance sheet growth and the S&P 500’s monster rally of the past dozen years? I doubt it.

Figure 8

Such extreme housing price inflation wasn’t always the case. From 1899 through 1999, U.S. home prices increased at roughly the inflation rate which, prior to the creation of the Fed in 1913, was essentially zero. Prices actually fell, adjusted for the CPI in the 1920s (surprisingly, considering those were boom years) and didn’t take off until the inflationary years after WWII. (In Chapter 16, we’ll look at the overall change in consumer prices since the Fed came into existence vs prior to 1913.)

Figure 9

Interestingly, even the semi-inflationary 1960s and the very inflationary 1970s didn’t see meaningful price rises, after adjusting for the CPI. Nevertheless, since 1963, the median sales prices have vaulted from $158,000 in today’s (rapidly depreciating) dollars to $350,000. Obviously, something changed around 2000. Could that something be Bubble 1.0? Or, more to the point, was it the bursting of Bubble 1.0 and the caving in by the Fed to calls for it to create another bubble, as Paul Krugman repeatedly did?

To reiterate one of this book’s main themes, it was the tech-wreck of that year which panicked the Fed into slashing rates down to levels unseen since the Great Depression. Then it left them there for years even as the economy began a steady, if unspectacular, recovery from the twin shocks of that market crash and the horrors of September 11th, 2001.

By the time the Fed began to raise rates, from a microscopic 1% in June 2004, the housing market was already ripping, as you can see from Figure 3 above. It then compounded its excessively easy money mistake by only glacially raising rates. Moreover, it did so in such a predictable way that neither the housing market nor the stock market were in the least bit rattled.

Senior Fed officials would subsequently admit that this predictability eventually led to extreme volatility. In this regard, it was the housing bubble and crash that focused tremendous academic and media attention on a deceased and formerly obscure economist, Hyman Minsky. It was Professor Minsky who articulated the basic premise that “stability breeds instability”.

The highly predictable and languid monetary tightening the Fed affected between 2004 and 2007 was a classic example of this phenomenon. It was this era that was the highwater mark of the so-called Great Moderation, an economic phase supposedly deftly orchestrated by the Fed’s former “Maestro” Alan Greenspan and then carried on by his hand-picked successor, Ben Bernanke. It was a blissful time of low inflation, long bull markets in stocks, and generally healthy economic conditions. Some have referred to it as a “Goldilocks” phase — neither too hot nor too cold. (Please see the Appendix for more on Mr. Greenspan and his de-deification.)

In hindsight, the Great Moderation was precisely the kind of long-lasting stability that Professor Minsky was warning about years earlier. Once the mortgage market came off the rails in the summer of 2007 – with the sudden collapse of two hedge funds that were leveraged investors in the sub-prime mortgage space—housing had its “Minsky Moment”, as Pimco’s then Vice-Chairman Paul McCulley presciently proclaimed at the time.

The reality is that long periods of stability and predictability, not to mention overly easy monetary policies, encourage consumers and institutions to get out over their skis on the risk spectrum. Leverage is increasingly used to goose returns. It rises to the point that any serious price correction has the potential to turn into a self-reinforcing chain reaction of selling and involuntary liquidation (like margin calls in the financial markets and bank foreclosures leading to distressed sales with real estate).

The detonation of the enormous housing bubble of the first decade of this millennium/century was indeed Professor Minsky’s moment. It shook the global financial system to its core and nearly created its Thelma & Louise, off-the-cliff, ending. Without question, the Fed and the other leading central banks deserve plentiful praise for the emergency measures they took in avoiding an economic and financial apocalypse. But — and this is a huge “but” — their complacency as Bubble 1.0 and, especially, Bubble 2.0 engulfed most of the Western world was inexcusable.

And, certainly, their prior bubble-blindness was what necessitated their extraordinarily creative responses to the Global Financial Crisis. As the aforementioned financial commentator extraordinaire Jim Grant has often quipped, the Fed and its peers act as both “arsonists and fire brigade”. In my mind, that’s simply a pitch-perfect phrase.

The aftermath of the housing/mortgage crisis that began in the seemingly tranquil summer of 2007 still haunts us today. It is why the world continues to have some $10 trillion of negative-yielding bonds in existence. It’s also why central banks, including the Fed, can’t kick the habit of massive money manufacturing. The Boomer generation of retirees and near-retirees is particularly imperiled by the extermination of interest rates, as are the savings industries of the West such as pension funds, insurance companies and banks.

As many other pundits have pointed out, capitalism doesn’t work very well in the absence of interest rates, a sentiment with which I vigorously concur. For now, that reality is being obscured by mostly bubbly financial markets. But when artificially elevated asset prices revert to the mean, and quite possibly crash, the fragility of the situation will be revealed. When that day arrives, it will be a very mean reversion indeed.

[i] In reality, QE actually was the creation of digital reserves that the Fed used to buy treasury bonds from the banking system.

[ii] Although the Fed was reluctant to call its various money fabrication schemes QE, almost everyone else did; for some reason it prefers the term Large Scale Asset Purchases.

[iii] Roman emperor, Vespasian, once quipped, when he was criticized for taxing public toilets, “Pecunia Non Olet”, “Money doesn’t stink,” and I suspect all the newly minted centimillionaires and billionaires would agree.

[iv] Covid has only accelerated this process. The total wealth of the planet’s billionaires increased from $5 trillion to $13 trillion from the March 2020, market bottom through March of 2021. This was the greatest asset spike ever recorded on the Forbes’ billionaire list. (Source: Grant Williams’ Things That Make You Go Hmmm, July 2021)